Does being on a path to diabetes affect your brain?

As adults age, their weight, blood pressure, blood sugar and triglycerides tend to creep upward. Higher levels of these factors raise the risk of heart disease and Type 2 diabetes, but what is it doing to the organ that’s the seat of our intellect?

A 2015 review article in Diabetes Care showed that people with Type 2 diabetes, also called adult-onset diabetes, are 60% more likely to develop dementia than those without diabetes. The reasons for this are unclear, however. A study led by Dr. Bradley MacIntosh, a senior scientist at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) who specializes in brain imaging, may shed light on this question.

In a paper published in Human Brain Mapping in October 2019, MacIntosh and Dr. Walter Swardfager, scientists in the Hurvitz Brain Sciences Research Program at SRI, found diabetes-related traits were associated with decreased blood flow in two-thirds of the grey matter cerebral regions they studied. Grey matter, a ribbon of tissue that encompasses the brain’s surface, serves to process information.

“We used cerebral blood flow, because we think that it can tell us a little bit about how active and supported different parts of the brain are,” says MacIntosh, who is also an associate professor of medical biophysics at the University of Toronto. “Blood flow could be high in a brain region because it is working harder, and cerebral blood flow is providing the necessary oxygenated blood to keep that brain region going.”

The team looked at the health data of 451 Americans who were around 50 years of age. Nearly all of them—97%—did not have diabetes. The participants were a subset of more than 5,000 men and women who had enrolled in a study following them over time to understand the development and causes of cardiovascular disease. The study, initiated in 1984, is called coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA, for short). The original study has since expanded in scope by including brain imaging. It has spawned hundreds of research papers.

MacIntosh contacted the CARDIA investigators and secured access to the participants’ information. This included MRI brain scans, body mass index (BMI), waist size, blood pressure, fasting glucose and insulin levels, and results from an oral glucose tolerance test, which measures how well your body regulates blood sugar two hours after consuming a very sweet drink.

Two newly minted PhDs, Drs. Zahra Shirzadi and Sarah Atwi, members of the MacIntosh lab, helped to analyze the data. They found that higher fasting blood sugar and insulin, high blood sugar after the glucose tolerance test, lower high-density lipoproteins (“good” cholesterol), higher triglycerides, large waist size and high BMI were correlated with decreased blood flow in the brain.

MacIntosh notes the effect was almost across the board. “Which brain region cares about your diabetes risk profile? Sixty out of the 90 regions we looked at. Two-thirds of the brain is potentially implicated,” he says.

Diabetes-related risk factors were also connected to weaker performance on memory tests in which, for example, participants had to recall a list of items recited to them by a researcher.

“As the diabetes risk profile increased, memory performance worsened, and, at the same time, cerebral blood flow was reduced,” says MacIntosh. “You can think of these two developments walking hand-in-hand down a path that can lead to bad brain outcomes,” he says.

“[The results] suggest that even in people without diabetes, we still see an effect of vascular and metabolic risk factors on the brain,” says Swardfager. “It gives you pause. How is this combination of factors affecting the brain even before your doctor might say, ‘this is a problem for you?’”

The findings are instructive given that, according to Diabetes Canada, 6 million Canadians have prediabetes. Here, blood sugar is a little high, but not high enough for someone to be diagnosed with diabetes. Moreover, 3 million Canadians have diabetes, with 200,000 new cases being diagnosed each year. Most people who have diabetes will have prediabetes first.

The researchers’ study adds to evidence that the brain is affected even before diabetes is diagnosed. “If you haven’t paid that much attention to your health and you happen to be 50, now is the time [to do so], for sure,” says MacIntosh. “It seems as though once you start to pile on three or four risk factors, those are definitely warning signs. That’s happening at midlife.”

Swardfager, who is also an assistant professor in the department of pharmacology and toxicology at U of T, echoes this sentiment. “Lifestyle and genetics play roles in how your cognition is going to decline as you age. If you can eat healthy, exercise regularly, even at a low intensity, and control risk factors as soon as they start to arise with recommended medications, it will be beneficial—and earlier is better, because here we saw effects at age 50—a decade or two before dementia becomes obvious in most cases,” he says.

Noting that diabetes is a risk factor for stroke and dementia, MacIntosh says that uncovering how the condition may be contributing to brain aging is critical to improving outcomes, especially given its prevalence. “We want people to recover after a stroke, and in people that have neurodegeneration, we’d like to harness the brain’s resilience. I think that diabetes is acting against our efforts on those two fronts. If we want to do better on those brain outcomes that are pretty nasty to society and people, then we need to think about diabetes.”

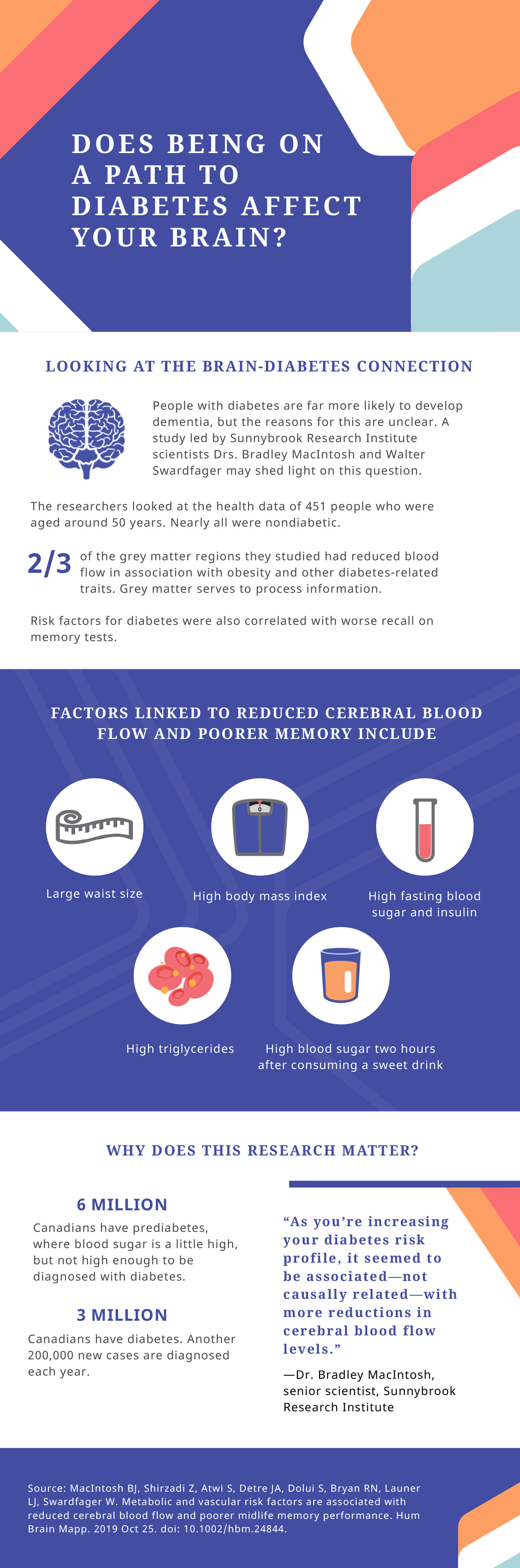

Read text-only version of above infographic

Does being on a path to diabetes affect your brain?

Looking at the brain-diabetes connection

People with diabetes are far more likely to develop dementia, but the reasons for this are unclear. A study led by Sunnybrook Research Institute scientists Drs. Bradley MacIntosh and Walter Swardfager may shed light on this question.

The researchers looked at the health data of 451 people who were aged around 50 years. Nearly all were nondiabetic.

Two-thirds of the grey matter regions they studied had reduced blood flow in association with obesity and other diabetes-related traits. Grey matter serves to process information.

Risk factors for diabetes were also correlated with worse recall on memory tests.

Factors linked to reduced cerebral blood flow and poorer memory include: large waist size; high body mass index; high fasting blood sugar and insulin; high triglycerides; and high blood sugar two hours after consuming a sweet drink.

Why does this research matter?

Six million Canadians have prediabetes, where blood sugar is a little high, but not high enough to be diagnosed with diabetes.

Three million Canadians have diabetes. Another 200,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.

“As you’re increasing your diabetes risk profile, it seemed to be associated—not causally related—with more reductions in cerebral blood flow levels.” — Dr. Bradley MacIntosh, senior scientist, Sunnybrook Research Institute

Source: MacIntosh BJ, Shirzadi Z, Atwi S, Detre JA, Dolui S, Bryan RN, Launer LJ, Swardfager W. Metabolic and vascular risk factors are associated with reduced cerebral blood flow and poorer midlife memory performance. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019 Oct 25. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24844.

The CARDIA study is funded by the U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

MacIntosh’s research is supported by the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). His lab is part of the Centre for Research in Image-Guided Therapeutics at SRI, which was funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation. Swardfager’s research is supported by the Alzheimer’s Association, Brain Canada, CIHR and NSERC.

Original article: MacIntosh BJ, Shirzadi Z, Atwi S, Detre JA, Dolui S, Bryan RN, Launer LJ, Swardfager W. Metabolic and vascular risk factors are associated with reduced cerebral blood flow and poorer midlife memory performance. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019 Oct 25. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24844.