Elevating the LGBTQ presence in science and research

Dr. Jill Tinmouth has always attended hospital events alone, or opted to forgo them. In October 2018, however, she broke tradition. Accepting Sunnybrook’s department of medicine senior investigator award at a dinner in Toronto, Ont., the scientist in the Odette Cancer Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) and a physician at Sunnybrook brought her spouse, Dianne.

Tinmouth reflects on her past choices not to bring Dianne to hospital functions, some of which she says could have been unconscious. She does this in the context of a greater discussion around the experiences of LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) people in science and research.

Although Tinmouth hadn’t brought her partner to a hospital event until fall 2018, she has been out since her first year of university. She has revealed her sexual orientation to colleagues, often through conversations about her partner. “I try to live my life the way that someone who’s straight would live in the workplace. People talk about their kids or their spouse; well, I talk about my partner. That’s my main way of being a full person in the workplace,” she says.

“That’s a privilege for me, because not every person is partnered,” adds the associate professor at the University of Toronto, whose research has had demonstrable impact on health policy in Ontario. A focus of her work is cancer screening in the province’s Indigenous populations, with the aim of boosting this group’s low screening participation.

Benoît Chambaron agrees that coming out is easier when in a relationship. The manager of comparative research at SRI routinely travels to visit his partner. He says discussing weekend plans, for example, is an opportune time for a person with a significant other to share their sexual orientation, and being open about this enhances job performance. “Not having to hide yourself helps you to be better at work,” he says.

Tinmouth chimes in about the detriments of remaining hidden: “If you’re in the closet, you’re taking, say, 25% of your willpower, concentration, thoughts and effort just to stay in the closet. That’s 25% less that you have for your work, life or family.” She says the collaborative component of her job—engaging with different people on a daily basis—is one of her role’s pleasures. “If you can’t feel like you’re your full self in those interactions, that can feel stressful, and I think it does take away from productivity.”

Also connecting productivity to being one’s full self at work is a long-time peer of Tinmouth’s, Dr. Matthew Cheung, an openly gay associate scientist in the Odette Cancer Research Program at SRI and a hematologist at Sunnybrook. “For us to be the most productive and excellent at what we do, we need to be comfortable with who we are. We can’t feel uncomfortable coming to work and feeling like we have to shield or hide an aspect of ourselves from the people we need to relate to and interact with every day,” says Cheung, who is also an associate professor at U of T. His research uses large database studies to investigate how characteristics, including gender and immigration status, have an impact on access to cancer screening and treatment, and the affect this has on health outcomes.

For some, a component of being comfortable as an LGBTQ person in science and research is knowing others who identify similarly. In certain workplaces, this is difficult—only 3% of 30,000 people in six science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)-related federal agencies in the U.S. identify as LGBT. (Canadian numbers are publicly unavailable, to the best of our knowledge.) There’s no figure for SRI’s LGBTQ population, but Chambaron says he only knows one other openly LGBTQ person at the institute. That’s more than Grey Kuling knows.

Kuling, who identifies as gay, is in the second year of his PhD. Within medical biophysics at U of T, the program through which he studies, he thinks there’s one other LGBTQ person, though he doesn’t know this student’s name. “Unfortunately, I don’t know many [LGBTQ people] in research. That’s one of the topics I find troubling; as I get higher and higher up, there’s less and less people who also identify as gay or lesbian,” he says.

Asked about whether an organized group of LGBTQ people at SRI would be a welcome addition, Kuling is candid: “Sometimes I have difficulty connecting with other researchers. They all seem to have groups—extracurricular things, like sports or games or movie nights. I feel like something more specific to what I identify with, like being LGBTQ, would be nice to have. Just to come together and discuss things and hang out. It’s a good release; it’s a community thing.”

Kuling does his research in the lab of Dr. Anne Martel, a senior scientist in Physical Sciences at SRI, who recently shared her thoughts on being a woman in science. He analyzes MRI scans of breast tissue to determine which women are at risk of developing breast cancer. To do this, he uses machine learning, whereby computers “learn” features of tissue, thus enabling them to distinguish between high- and low-risk patients.

Cheung also emphasizes the benefits of knowing other LGBTQ staff. “It’s vital,” he says. “To be able to know you can reach out to anyone at any point who identifies with what you’re going through, I think that’s really important.” For him, one of those people has been Tinmouth: “I feel like I’ve always been supported here, but I think it helps to know I can walk over to where Jill is.”

It’s comforting for LGBTQ people to know they’re not alone in science and research, but it’s also encouraging to see themselves reflected among those in senior positions. On this note, Tinmouth discusses her years as a student, where she says there were few LGBTQ physicians at her medical school. As a result, she became involved with a national organization that arranged yearly conferences for LGBTQ students to attend, and where out physicians, some of whom were successful researchers, would speak. “That was really critical in terms of feeling like, ‘This is somebody who’s made it through, who is OK and can be open.’ It was terrifically important,” she says.

Tinmouth took this concept of community and ran with it. During her residency at U of T, she created a similar group for LGBTQ physicians. One of the members was Cheung. “It was quite helpful to me. Jill is a few years ahead of me, but the people in this group—and there were upwards of 20 or 30—were in all aspects of their careers. There was a strong sense that, ‘Hey, it’s OK. You can do everything you want to do, you can be promoted, and you can be very active scientifically,’” he says. “This set-up, where you could see mentors who were gay and were comfortable with it, and were able to achieve, that really grounded it for me in terms of not having to worry.”

Having LGBTQ people on staff and involved with projects is part of creating a dynamic—and improved—workplace. Thanks to the federal government’s commitment to equity, diversity and inclusivity (EDI), and resulting changes to the Canada Research Chairs Program, there’s been a push to incorporate EDI policies across the country’s research institutes. This has been fully embraced by SRI.

“Diversity makes the enterprise better,” Tinmouth says. “Bringing a different perspective, experience, way of thinking—whether it’s about sexual orientation or gender or ethnic identity or religion—diversity, and an environment that welcomes diversity, makes for a better, more productive research experience and likely better science.”

Chambaron reiterates the benefits of diversity. “At any level within a workplace, it’s important to have well-balanced representation,” he says. Not only does it generate a wealth of perspectives, but having a well-rounded team also encourages people of visible and invisible minorities to participate, he adds. “The minute you can relate to someone, it brings a certain comfort. It helps people accept themselves as well.”

Comfort and EDI are mentioned by Kuling, too: “I think shedding light on people who are discounted for certain identities helps to even out the playing field. People will only become successful if they’re comfortable with themselves and comfortable around the people they interact with.”

Transporting herself back to the dinner where she received her senior investigator award, Tinmouth admits she was a bit nervous and anticipated discomfort about bringing Dianne. Her concern proved unwarranted, though, as she and Dianne were warmly received. “What was really nice was that a number of people made a special effort to come over, say ‘hi’ and make us both feel welcome. That was significant. It was really gratifying to see how welcoming the Sunnybrook community was,” she recalls.

“I’ve felt very lucky here. I feel very supported, and it’s been great,” she adds. “I think there’s ample room today to be an LGBTQ scientist.”

Read text-only version of above infographic

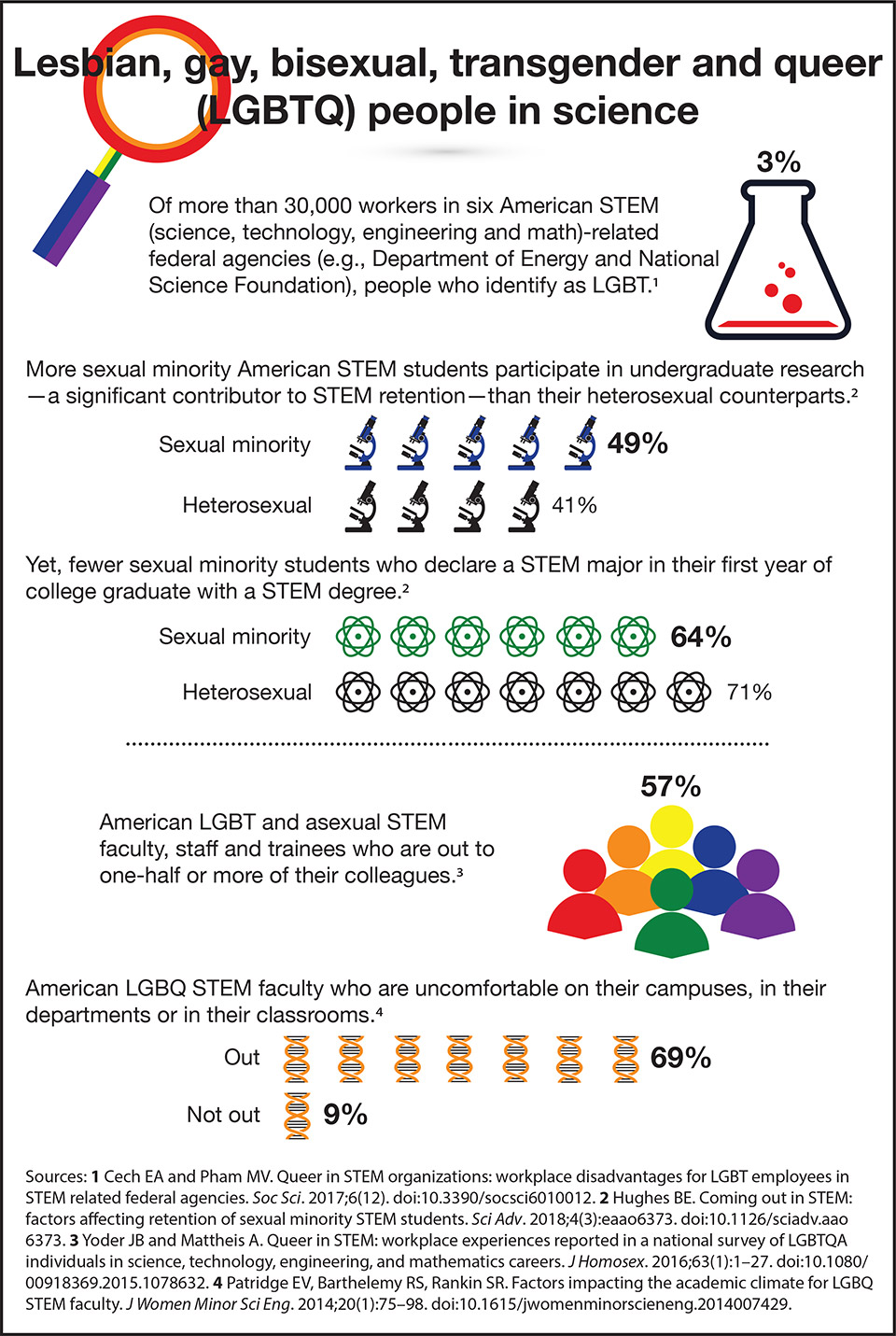

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people in science

3% of more than 30,000 workers in six American STEM (science, technology, engineering and math)-related federal agencies (e.g., Department of Energy and National Science Foundation) identify as LGBT.1

More sexual minority American STEM students participate in undergraduate research—a significant contributor to STEM retention—than their heterosexual counterparts.2

Sexual minority: 49%

Heterosexual: 41%

Yet, fewer sexual minority students who declare a STEM major in their first year of college graduate with a STEM degree.2

Sexual minority: 64%

Heterosexual: 71%

57% of American LGBT and asexual STEM faculty, staff and trainees are out to one-half or more of their colleagues.3

American LGBQ STEM faculty who are uncomfortable on their campuses, in their departments or in their classrooms:4

Out: 69%

Not out: 9%

Sources: 1 Cech EA and Pham MV. Queer in STEM organizations: workplace disadvantages for LGBT employees in STEM related federal agencies. Soc Sci. 2017;6(12). doi:10.3390/socsci6010012. 2 Hughes BE. Coming out in STEM: factors affecting retention of sexual minority STEM students. Sci Adv. 2018;4(3):eaao6373. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao6373. 3 Yoder JB and Mattheis A. Queer in STEM: workplace experiences reported in a national survey of LGBTQA individuals in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. J Homosex. 2016;63(1):1–27. doi:10.1080/00918369.2015.1078632. 4 Patridge EV, Barthelemy RS, Rankin SR. Factors impacting the academic climate for LGBQ STEM faculty. J Women Minor Sci Eng. 2014;20(1):75–98. doi:10.1615/jwomenminorscieneng.2014007429.

Cheung receives donations from Roy and Marjorie Linden, and Joan Fisher and James Rowland. Tinmouth’s research is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

In a nutshell

- Out staff at Sunnybrook Research Institute share their thoughts on being a minority group in science.

- They touch on being one’s full self at the workplace and seeing LGBTQ representation in senior positions.

- Having an organized group of LGBTQ people at SRI is an idea they agree would be beneficial.