Charlotte’s OCD was debilitating but Sunnybrook’s new residential program, through the Frederick W. Thompson Anxiety Disorders Centre, has helped her manage the compulsions and obsessions that trapped her in her home for years.

Charlotte lived with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) so severe that she couldn’t leave her home. Her symptoms began when she was just 8 years old – if things in her room were moved, she would be anxious until they were back in

the right place. When her parents left for work, she would worry that something bad would happen to them. Charlotte thought this level of stress was normal, and her family thought she was just a particularly anxious child, but

things got worse.

Charlotte began to perform lengthy routines, fearing that if she didn’t, awful things would happen to the people she loved. In her last year of high school, she would brush her teeth multiple times, fold laundry repeatedly,

and turn lights on and off, fearing that if she didn’t, her ailing grandmother would die.

I was so tired, and so drained. I had no fight left.

Struggling to cope

Her symptoms became aggressive when Charlotte left home for university. With a full course load and living with people she didn’t know, Charlotte struggled to take on school and maintain her independence. Her fears about her family

getting hurt led to compulsions and obsessions that began to take control of her life.

“I knew I had OCD, but I was afraid to tell anyone.”

She sought help from her family doctor. However, it was difficult for her to be open about how much it had affected her. “I was ashamed, and I wasn’t truthful, so I was misdiagnosed.”

Charlotte was given medication, and she went back to school. Her routines became long, onerous ordeals. She would spend hours doing laundry, turning lights on and off, putting things away and taking them out again, tapping

objects, and pacing back and forth. She began missing classes because the five-minute walk to campus would take her over four hours.

Out of options

Things got worse, and Charlotte was finally ready to be honest about her condition. Her doctor referred her to a specialist who started her on new medication and cognitive- behavioural therapy. But the medication didn’t help, and Charlotte

often missed her appointments with her therapist because she was trapped in her house in a cycle of obsessions and compulsions she needed to act out so her sister and parents wouldn’t get into an accident.

“Every day I’d wake up and think, ‘It can’t get worse than this,’ and then I’d wake up a week later, and it would be worse.”

After graduating, Charlotte lost hope for her future. She was hospitalized with suicidal thoughts. While in the hospital, she met with psychiatrists who recommended a day program at another hospital. Charlotte agreed to

go, but it wasn’t enough.

Charlotte’s team of doctors and therapists, her family, and Charlotte herself knew that she needed a residential program, but the only programs available at the time were in the United States, and OHIP denied her request

for funding. Out of options, Charlotte attempted suicide.

“I was so tired, and so drained. I had no fight left.”

A life saved

Charlotte was airlifted to an ICU in Toronto, where she spent three days; one of which was in a coma. Just when things were at their worst with no sign of hope, her family was contacted by Sunnybrook. The hospital was opening Canada’s

first residential program for severe OCD, and wanted Charlotte to be one of the first patients.

In her first week in the Frederick W. Thompson Anxiety Disorders Centre’s Intensive Treatment Program for OCD, Charlotte knew it would work. “Having the 24-hour care that I needed made a difference. If I couldn’t make

it down to a session, someone would come up and check on me. ”

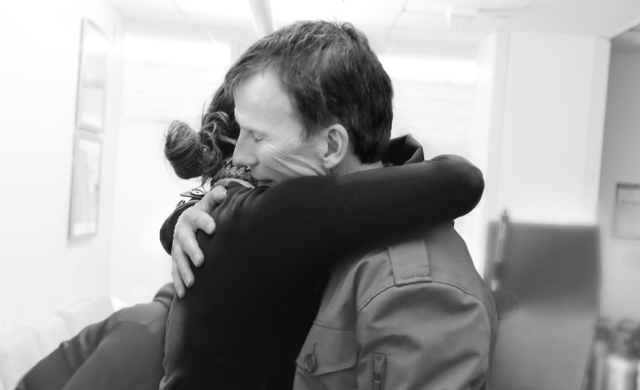

Charlotte was an inpatient for 14 weeks. Her parents and sister came to meet her for family sessions with the team, and she was able to go home on the weekends. These home visits were crucial for identifying things she

needed to work on so she wouldn’t relapse when she was released. “My doctors made me feel welcome, normal, and understood. Sunnybrook saved my life.”

A new chapter

When Charlotte entered the program, she had “massive” routines around everything she did during a day. A task that would take her family ten minutes would take her two hours. Now, she can take her dog outside and play. She can go to

the grocery store and cook for her family, and she enjoys it. She still struggles with obsessions and compulsions, but with the tools she learned at Sunnybrook, they are manageable, and become more so every day.

“Sunnybrook gave me my life back. I didn’t have any satisfaction in living. Being able to get up and not dread the day is a joy.”

HELP US MAKE STORIES LIKE charlotte’S POSSIBLE

Donate Now