All POCUS, no HOCUS

Bedside imaging, also known as point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), is emerging as a powerful, evidence-based tool in the ER

June 12, 2017

Dr. Jordan Chenkin (far right) and his colleagues in Sunnybrook's trauma bay use point-of-care ultrasound to help expedite diagnoses.

The case is one of the more memorable ones of Dr. Jordan Chenkin’s career: a 38-year-old woman who seemed well walked into Sunnybrook’s emergency department (ED), where Chenkin is a staff physician, complaining of blurry vision.

Her breathing was normal, and there were no problems with her brain or heart. She was triaged to the “purple zone,” designated for minor conditions. The only abnormality was high blood pressure, common in anxious patients. Chenkin tried examining her eyes with a lens that shines light into the back of the eye, but couldn’t get a good view. Determined to get to the bottom of her troubles, he pulled out one of the department’s portable ultrasound units. Gliding the probe gently over each closed eye, he had his answer: retinal detachment.

It is rare for both retinas to detach simultaneously. A common cause of the condition is preeclampsia, a complication of pregnancy that’s characterized by high blood pressure. Chenkin ordered a blood test, which, to the patient’s utter shock, revealed she was pregnant. He knew that to relieve her high blood pressure she would need to give birth immediately; delaying it would increase her risk of stroke, seizure or coma. But first he had to determine how far along in the pregnancy she was. With the same ultrasound unit, he measured the fetus’ head circumference, which is used to calculate gestational age. At 26 weeks, the baby, if delivered, had a relatively good chance of survival.

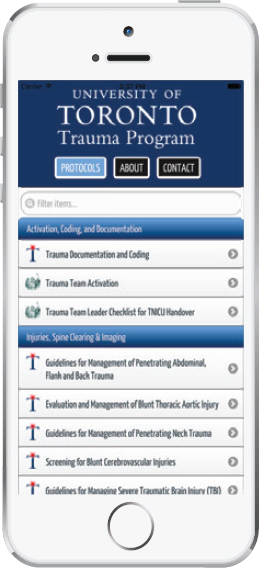

Not sure how to treat a trauma patient?

Naturally there’s an app for that.

The University of Toronto Trauma Protocols app was created by Dr. Avery Nathens and U of T trauma residents.

The University of Toronto Trauma Protocols app was created by Dr. Avery Nathens and U of T trauma residents.

The app provides best practice guidelines on how to treat traumatic injuries.

The guidelines were developed with input from trauma team leaders at U of T and are updated regularly.

22,095 downloads since 2013

22,095 downloads since 2013

Before the app, “residents would not necessarily do the right thing,” says Nathens. This would often lead to extra procedures and tests, which would in turn cause delays in treatment. “The app puts everybody on the same page,” he says.

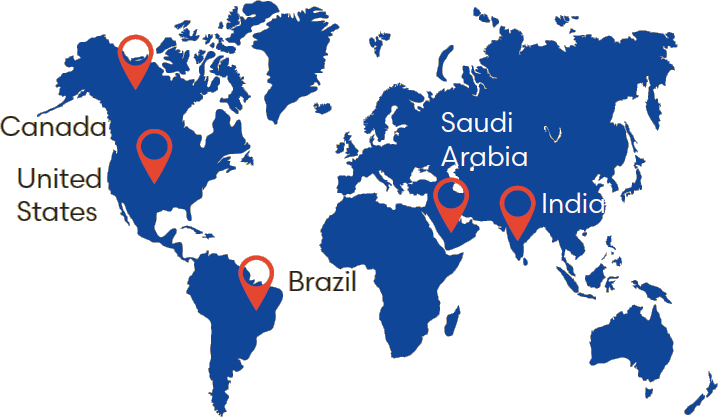

The app has been downloaded in 150+ countries

Five countries with the most downloads: Canada, United, States, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, India

"This was just going to be a U of T thing, but now I go to meetings and people are talking about this app. I’m amazed at how popular it is." — Dr. Avery Nathens

“She went from walking into the minor area of the ED to going to the operating room for an emergency C-section within a few hours,” says Chenkin, a researcher in the Tory Trauma Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI). Following up, Chenkin learned that his patient’s vision had returned to normal after delivery and she and her baby were well.

The case, which he reported in the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, highlights the utility of point-of-care ultrasound, sometimes abbreviated as POCUS. This is imaging done by doctors on their patients, which is why it is also called bedside ultrasound. The technology is gaining traction in the ED; as Chenkin notes, there is a difference between bedside ultrasound and that done by radiologists. Emergency doctors use ultrasound during physical exams to troubleshoot ailments efficiently, whereas radiologists use it to perform comprehensive exams. “This is a tool that can help you make better decisions more quickly. It helps free up some of that burden of the long differential diagnosis we face with a lot patients. You can cross a lot of things off that list and make it a little bit easier to manage high volumes of patients,” says Chenkin.

Trauma care was the catalyst for bedside ultrasound in the ED, says Chenkin, because it can immediately show life-threatening conditions like fluid around the heart and internal bleeding. “The core applications are designed for the sickest of the sick patients. You have a patient who’s dying in front of you, and before ultrasound you had to go with your best guess as to what was going on, but now you can actually rule things in and out pretty quickly,” he says. Point-of-care ultrasound also expedites diagnosis of other grave conditions like abdominal aortic aneurysm, which is a bulge in the main vessel that carries blood from the heart to the rest of the body, and ectopic pregnancy, where the fetus grows outside the uterus.

The popularity of bedside ultrasound is growing, but there are two issues: a knowledge gap regarding best use of the technology, and challenges in training doctors in how to use it. Chenkin is addressing these concerns through research and his role as a clinician-educator. In addition to teaching emergency doctors across Canada how to do ultrasound imaging, he is also director of point-of-care ultrasound for the division of emergency medicine at the University of Toronto.

He led a study showing web-based learning is effective in teaching doctors to use ultrasound to check for proper placement of a breathing tube. This work, which was published in Critical Ultrasound Journal in 2015, found that emergency physicians could learn this skill by watching a web tutorial and studying sample cases online. After just two practice attempts, all 66 doctors in the study could consistently identify when a breathing tube was placed correctly in the trachea, as opposed to the esophagus, an error that can cause brain damage due to lack of oxygen.

He is also looking at bedside ultrasound to screen people in the ED who’ve had a “mini stroke,” which is a temporary obstruction of blood flow to the brain. He will study how well ultrasound detects blockages in the carotid arteries, major blood vessels that supply blood to the brain, neck and face, to identify people at high risk of stroke.

Chenkin says that because Sunnybrook is a teaching hospital, he is able to consult with experts from every specialty. The hospital is building on the strength of its human resources by creating state-of-the-art infrastructure to optimize care of complex patients who might benefit from point-of-care imaging technologies. Plans are underway to construct a hybrid operating room (OR) equipped with advanced imaging and surgical devices. The facility will have the standard features of an OR, along with a CT scanner and angiography equipment used in cardiac procedures.

Having diagnostic and surgical tools in one space will save time and reduce the risk of further injury to patients by not having to move them to different parts of the hospital. Expediting treatment could make all the difference, as it did for Chenkin’s patient whose pregnancy had caused potentially fatally high blood pressure. Moreover, specialists of different stripes will be able to work side by side; a trauma surgeon could work on stopping abdominal bleeding while a neurosurgeon operates on the brain.

“It will be a game changer,” says Dr. Avery Nathens, director of the Tory Trauma Research Program at SRI and surgeon-in-chief at Sunnybrook. “Surgeons will be able to perform complex image-guided procedures with the ability to switch to open surgery, if needed; similarly, surgical procedures will be more precise with the availability of imaging. A hybrid OR means we will never have to compromise in our approach.”

Chenkin’s research was supported by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Sunnybrook and the University of Toronto.