Undaunted: journey through trauma

One man’s story of survival and healing

June 12, 2017

Don’t move, don’t move. They’re collecting parts of your leg.

Namir Mohammed Hussain was severely hurt in a motorcycle crash. He was rushed to Sunnybrook, where his injuries sparked a massive activation of the trauma team.

Sitting in his bed at Sunnybrook’s trauma ward, Namir Mohammed Hussain thinks back and laughs at the absurdity of those words etched forever in his mind. It is Oct. 13, 2016, nearly one month after the crash that almost claimed his leg. “I don’t remember anything [about the crash],” says Mohammed Hussain. “As soon as I hit the tire, I went completely blank.” What he does remember are the events leading up to the crash and being brought to Sunnybrook’s trauma centre. Despite the gaps in his memory, Mohammed Hussain says he is sure of one thing: had he been taken to another hospital that day, his outcome would have been very different.

On Sept. 16, 2016, Mohammed Hussain was riding his motorcycle on the highway when another driver merged into his lane and pushed him into the path of the eight-wheeler truck next to him. The 30-year-old father of two was travelling back from a meeting at the Loblaws office in Brampton to the Weston Foods headquarters in Etobicoke, where he worked as a software engineer. “When I woke up, I saw that I was on the road and lying down,” he says. “There was a guy standing next to me, and I asked him if he could help me take my leg out.” The passerby told him not to move and that they were collecting pieces of his leg. “That was so scary. I was awake, but I couldn’t feel the left side of my body.” His left leg had been run over by the truck and was pinned underneath it. Paramedics rushed to free Mohammed Hussain and bring him to Sunnybrook, one of only two Level 1 adult trauma centres in the Greater Toronto Area. He arrived with chest injuries, broken ribs, a fractured shoulder and a mangled left leg. “The primary focus was his leg, which was almost amputated,” says Dr. Avery Nathens, director of the Tory Trauma Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) and the trauma surgeon who oversaw Mohammed Hussain’s care. “Sometimes the easiest thing to do is to amputate, but our surgeons felt they should use all the tools in their armamentarium to try to save it.”

That decision fell to Dr. Diane Nam, the orthopaedic surgeon on call when Mohammed Hussain was brought in. “I was concerned about the blood supply at first because the left foot was cold and white,” she says. As she and her team stabilized the leg by carefully realigning the limb and removing dead tissue, warmth and colour returned to the foot—encouraging signs that the limb could be saved. As Nathens pointed out, however, retaining an arm or a leg can be harder for the patient than amputating one. Orthopaedic surgeons like Nam can repair bone, but for the limb to survive and be functional, they rely on the expertise of vascular surgeons to fix damaged blood vessels and plastic surgeons to mend nerves and obtain soft tissue coverage. “Limb salvage of a mangled extremity is our primary goal whenever possible,” says Nam, who is also an associate scientist in the Holland Bone and Joint Research Program at SRI. “But we can’t reattach a limb if there’s no blood supply, and the timing to restore this after injury is critical.”

The injuries he sustained to his chest and lungs meant that Mohammed Hussain had to be sedated and put on a ventilator to breathe for him for two days. During that time, an orthopaedic team led by Dr. Hans Kreder spent six hours trying to find a live nerve in his damaged leg before piecing the broken bits of bone back together. Soon after, a plastic surgery team led by Dr. Joan Lipa grafted skin from his right leg into the wound defects on his left leg. “When I woke up, I saw that my leg was pretty much tied with big rods and big screws on top,” says Mohammed Hussain. All told, he had three operations on his leg and one to fix his fractured shoulder.

Speaking from his hospital bed, Mohammed Hussain reflects on how lucky he is that he did not sustain any injuries to his head or internal organs, and how fortunate he is to have been brought to Sunnybrook. He is grateful for the care he received here, but cannot wait to be home with his four-year-old daughter and 18-month-old son. “I miss my kids,” he says. “My daughter came, and she was like, ‘why are you not coming home? Why are you in the hospital?’”

Dr. Larry Robinson wrote the book on trauma rehabilitation.

“He has his leg, which is a big positive,” says Nathens. “He may not have had his leg if he had been at a community hospital. Saving an extremity requires a team of experts in orthopaedic trauma, plastic surgery and vascular surgery. There is good evidence to suggest that teams like we have at Sunnybrook have a tremendous impact on restoring function after injury.”

Improving function in trauma patients is also the focus of Dr. Larry Robinson’s work. Robinson is the director of the St. John’s Rehab Research Program at SRI and program chief for rehabilitation services at Sunnybrook. He is leading a project looking at whether early consultations with physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) specialists—also known as physiatrists—can shorten hospital stay and improve outcomes for trauma patients. The idea is based on a model of care in many U.S. trauma centres where such patients are seen by a physiatrist within days of admission. Early and regular care by a physiatrist helps identify potential complications and develop plans for discharge.

“Patients tend to fall between the cracks as they transition from the acute care hospital to rehab, and from inpatient to outpatient rehab,” says Robinson, who is himself a physiatrist. “This project is a way to overcome that. It will enhance the continuity of care and improve the patient experience as they traverse the continuum of care from injury to rehab.” The study will also contribute to the sparse literature on the impact of early PM&R consultations on acute care and rehabilitation outcomes. In a review of papers published between 1946 and 2015, Robinson and PM&R resident Dr. Alan Tam found only four that described the effects of a PM&R intervention on how patients fared. Although limited in number, these studies show benefits for patients receiving an early physiatry consult in areas such as post-injury pain and return-to-work rate. If successful, then Robinson’s study will strengthen the case for including physiatrists as part of the acute care team, and underscore their role in helping patients make the fullest recovery possible.

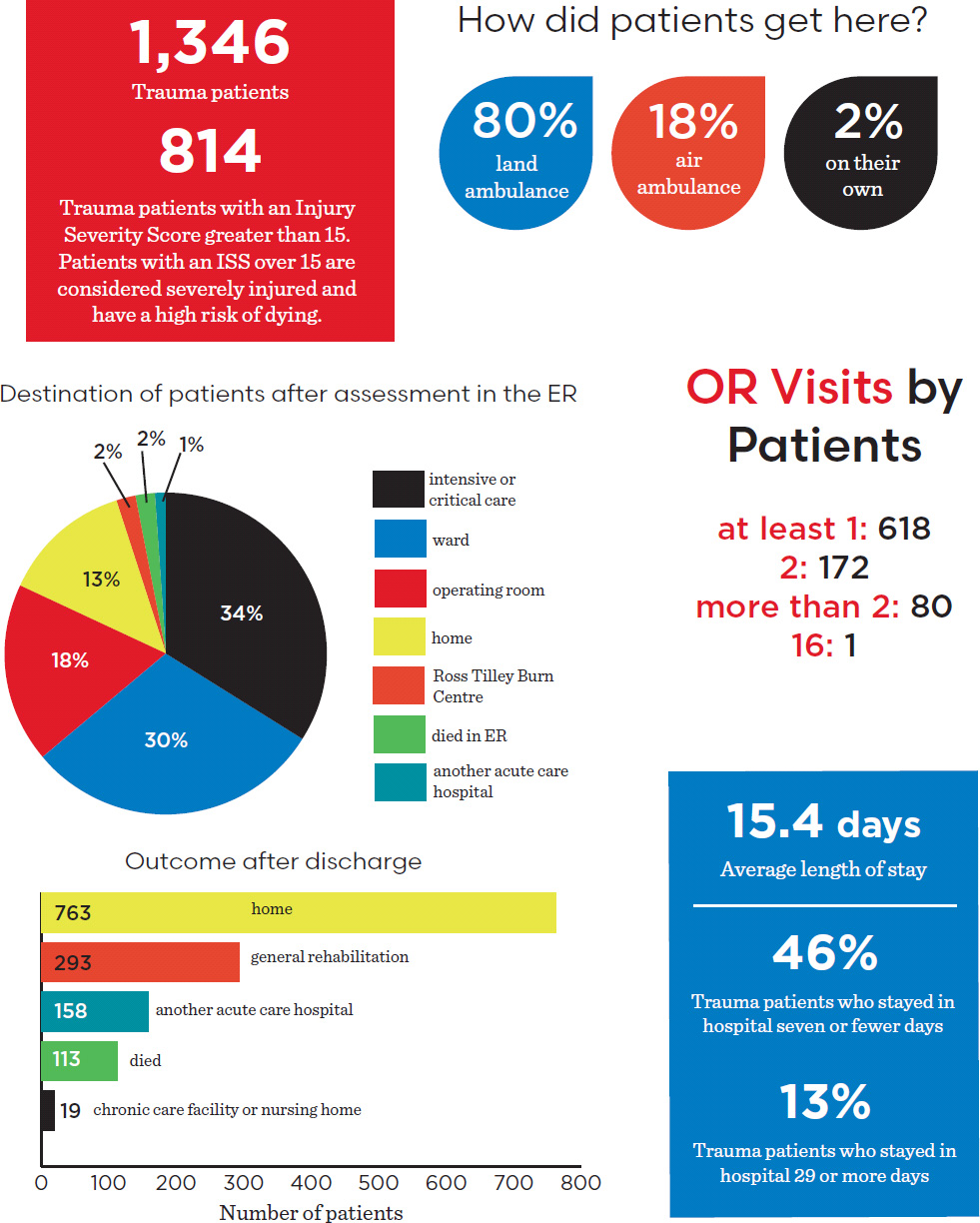

The trauma journey at Sunnybrook

Sunnybrook has the largest trauma centre in Canada. (It was also the first.) Sunnybrook's trauma centre is a Level 1 Centre—it cares for the most severely injured patients from across Ontario. The journey of a trauma patient like Namir Mohammed Hussain only begins upon arrival in the trauma bay. It is a long path to functional recovery.

Read text-only version of above infographic

The trauma journey at Sunnybrook

1,346 trauma patients

814 trauma patients with an Injury Severity Score greater than 15 Patients with an ISS over 15 are considered severely injured and have a high risk of dying

How did patients get here?

Land ambulance: 80%

Air ambulance: 18%

On their own: 2%

Destination of patients after assessment in the ER

Intensive or critical care: 34%

Ward: 30%

Operating room: 18%

Home: 13%

Ross Tilley Burn Centre: 2%

Died in ER: 2%

Another acute care hospital: 1%

OR visits by patients

At least 1: 618

2: 172

More than 2: 80

16: 1

Outcome after discharge

Home: 763

General rehabilitation: 293

Another acute care hospital: 158

Died: 113

Chronic care facility or nursing home: 19

Average length of stay: 15.4 days

Trauma patients who stayed in hospital seven or fewer days: 46%

Trauma patients who stayed in hospital 29 or more days: 13%

*Source: Data are from 2013–2014, as noted in the Sunnybrook Trauma Strategic Plan.

To that end, the researchers have started collecting data on trauma patients who were seen by a physiatrist within three days of admission and those who were not. The researchers will be following these patients for one year. Preliminary results suggest that involvement by a physiatrist significantly reduces a patient’s stay in acute care from 25 days to 16 days. Fewer days in acute care means these patients begin rehab sooner, although it is too early to tell what effect, if any, this will have on a patient’s ability to return to his pre-injury life. “Acute care has done a really good job of saving people’s lives,” says Robinson, who is also a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. “Our goal is to do a better job of giving patients their lives back.”

After seven-and-a-half weeks recovering in Sunnybrook’s trauma ward—his discharge was delayed when he developed a rash in response to the antibiotics he was taking—Mohammed Hussain began the next stage of his journey toward getting his life back. He arrived at Sunnybrook’s St. John’s Rehab Hospital in a wheelchair and left 15 days later walking on his own with a cane.

Today, he is back at home with his family and trying to return to his old life. He goes to physiotherapy three days a week for his shoulder, which is now strong enough to lift a bag and has enough range of motion to swing his arm. Months after his surgeries, Mohammed Hussain continues to experience pain in his leg. “There’s always pain but I believe that I have to live with it,” he says. “It’s not going to end in a day or two.” While the medications his doctors prescribed help to alleviate his discomfort, they can also interfere with the bone-healing process and could delay his recovery. Despite the setbacks—his first skin graft did not take so he underwent a second procedure in early January 2017—and the sometimes frustratingly slow progress, Mohammed Hussain remains optimistic and grateful. “I’m really thankful that I’m alive and that I’m getting back to my normal life,” he says. “It’s a long journey, but I’m lucky that I have my family and glad that I made it to here.”

Pain in the trauma bay

As an emergency department nurse for 11 years Thao Sindall has seen firsthand how inadequate early pain management can affect patients’ outcomes and perception of care in the trauma room. “Pain not being managed initially does lead to difficulties managing it later,” she says. Those challenges include longer hospital stays and chronic pain after discharge. Patients reported less satisfaction with their care because their pain wasn’t managed well while in the trauma room.

Sindall wanted to address the issues she saw through a quality improvement project of trauma patients during their initial stages of care. To carry out this work, she received the Sunnybrook Trauma Health Professions Innovation Fellowship, a partnership between the hospital’s Tory Trauma program and Practice-Based Research and Innovation.

“Because [Sunnybrook] is a teaching hospital and we have a lot of team members rotating through our doors, there isn’t a lot of consistency when it comes to the way we manage pain,” she says. “I really wanted to work on standardization so we can provide the best care to our patients.”

Patients arriving in the trauma bay do so in physical discomfort. “They’ve been hit by a car; they've fallen off a balcony. Oftentimes when we assess them, there are severe levels of pain,” says Sindall. Often, more urgent concerns—an obstructed airway or uncontrollable bleeding—push pain management to the bottom of the list of priorities. Sindall’s preliminary research found that the average time between arrival in the trauma room and first administration of pain medication was 19 minutes. “I’m looking to improve the time that we provide the first dose of analgesics,” she says. Her goal is to reduce that time by 30%. She believes that this would not only improve outcomes, but also patients’ satisfaction with their care.

In the first part of her project, Sindall interviewed nurses and trauma team members who work in the emergency department to understand their perception of pain management practices and to identify gaps in care. “Nobody thinks it’s their role to ask about pain,” she says. “So either everybody does it or nobody does it.” For the second part of her project, she is using the data she collected to develop and implement a strategy to enhance pain management in the trauma bay. Specifically, Sindall is exploring the use of visual cues to prompt nurses to include pain in their routine assessments. She hopes that by empowering her nursing colleagues to assume responsibility for the initial assessment of pain, patients’ suffering will be alleviated earlier and more effectively.

Robinson’s research is funded by an AFP Innovation Fund from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. He holds the John and Sally Eaton Chair in Rehabilitation Science.