Features

Messages

Digest

Short Stories

Abstracts

Attention: This Disease Is Deadly

Chances are more than one-quarter of people aged over 35 years will be diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in their lifetime.

Illustration: ©MaryLB/iStockPhoto

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a long-term lung disease that includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema. The World Health Organization predicts it will be the third most common cause of death by 2030, but the general public seems to know little about it. Dr. Andrea Gershon, a scientist in the Tory Trauma Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, led the first study to measure an individual's lifetime risk of developing physician-diagnosed COPD in a complete, multicultural, North American population.

Results, published in The Lancet, showed that 27.6% of people aged over 35 years are likely to be diagnosed with COPD in their lifetime—more than are likely to be diagnosed with congestive heart failure, heart attack, and breast, prostate and other cancers. These findings underline the societal burden of COPD, and the need for more resources and public health education to combat it.

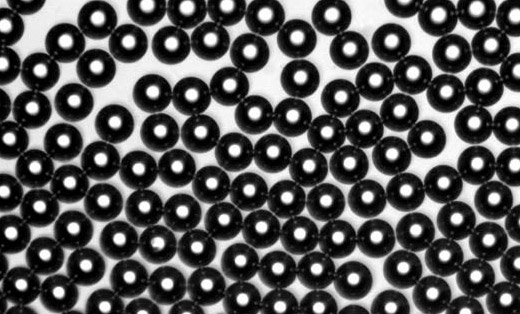

Pop Goes the Cancer

A deadly pairing: Ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles make tumours more sensitive to radiation. Here, actual microbubbles.

Photo: Sunnybrook Research Institute

Scientists at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) led the world's first preclinical study showing how pairing ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles with radiation enhances the effects of radiotherapy. Dr. Greg Czarnota, director of the Odette Cancer Research Program at SRI, led the study, which aimed to make tumours more sensitive to radiation and thus hasten their demise. Right now, an average of up to 35 small radiation treatments are needed to destroy a tumour.

Using ultrasound, the researchers burst microbubbles (tiny lipid-coated spheres of gas that can safely pass through the circulation) to weaken the blood vessels that feed tumours in a preclinical model of prostate cancer. They followed the microbubble treatment with radiation. Czarnota found just a single dose of radiation following ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles destroyed up to 50% of the tumour 24 hours after treatment, compared with 5% cell death using either ultrasound and microbubble treatment alone, or only radiotherapy, and thus representing an up to 10-fold greater cell kill.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows promise to increase the efficacy of radiation therapy at lower doses, which would mean less toxicity for patients and potentially fewer treatments overall.

Renaissance Cells

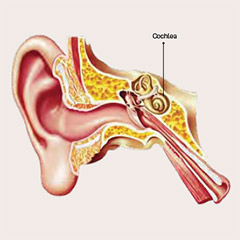

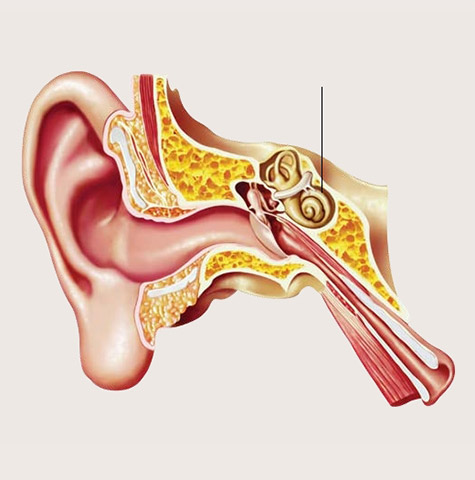

Mature mammals have a capacity for auditory hair cell regeneration, a finding that could spur new treatments for hearing loss.

Illustration: Leonello Calvetti/Shutterstock

Hearing loss is caused by damage to the auditory hair cells in the cochlea, the organ for sound. Hair cells, which are essential for balance, help convert acoustic energy into electrical signals that travel through the auditory nerve to the brain, where sound is interpreted. It's unclear whether lost hair cells are restored by cellular regeneration or repair, given in part that most damage doesn't result in the loss of all original hair cells. Recent studies have shown that some birds, after going deaf, were able to regenerate hair cells spontaneously and restore hearing.

Dr. Vincent Lin, an associate scientist in the Brain Sciences Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute, led a study that examined the regeneration of hair cells in preclinical models. The study's aim was to determine how new hair cells are formed in adult mice treated with an antibiotic that causes hair cell loss. Researchers looked at the rate of renewed hair cells and if manipulating a particular cellular pathway would enhance the growth process. They found that hair cell damage in the mice triggered and controlled supporting cells to regenerate into new hair cells, showing that mature mammals do have a natural capacity for hair cell regeneration. The study, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, may provide insight into the development of effective therapies to treat hearing loss.

PREDICTing Trouble

Spot this: An imaging marker on scans depicting the inside of the brain's blood vessels predicts which patients are at high risk for further bleeding in the brain.

Illustration: Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), when a blood vessel in the brain ruptures or leaks, accounts for up to 15% of all strokes and leads to about 40% of deaths. In patients with ICH, hematoma expansion soon after symptoms start highly predicts poor clinical outcomes, including early neurological deterioration and death. Needed is a way to determine which patients will have a hematoma expansion after ICH, so they can be treated promptly. Research suggests the "spot sign," an imaging marker that appears on a computed tomography angiography (CTA) scan, used to see inside blood vessels, may be one way to do this.

Drs. David Gladstone and Richard Aviv, brain scientists at Sunnybrook Research Institute, led the first multicentre, prospective cohort study to validate the CTA spot sign to predict bleeding in the brain in patients who have had a stroke or other ICH.

The study, aptly called PREDICT, enrolled 268 patients in six countries who presented with a brain bleed smaller than 100 ml less than six hours from first symptoms. Of 228 patients included in the primary analysis with a brain bleed, 61 were spot-sign positive and 167 were spot-sign negative. Presence of the spot sign predicted outcome, including hematoma growth, which was significantly more frequent and bigger in the spot-sign positive group. Moreover, clinical outcomes were worse, including mortality at three months: 43% of spot-sign positive patients died, compared with 20% of spot-sign negative patients.

The results, published in The Lancet Neurology, validate smaller studies of the utility of the CTA spot sign, and confirm it predicts which patients are at high risk for further bleeding in the brain and poor clinical outcomes.

- << Digest |

- Next: News

- |Short Stories >>