A fine balance

For patients vulnerable to developing sepsis while in hospital, how to balance the need for antibiotics against prudence in the face of increasing microbial resistance? Two docs take up the challenge

June 12, 2017

Patients in the intensive care or critical care unit receive around-the-clock specialized care. Even so, they are at higher risk of bloodstream infections, which in turn can lead to sepsis. Researchers are striving to make sure they get the decision about how long to treat patients with antibiotics just right.

Bloodstream infections are a common and serious problem that affects 15% of critically ill patients and an estimated 50,000 Canadians per year. Bloodstream infections arise when bacteria leaks into the blood, arising from an infection elsewhere in the body. They can lead to sepsis, a life-threatening condition. For trauma patients, whose wounds and injuries leave them susceptible to infection, avoiding sepsis becomes yet another hurdle to clear. Invasive life-support devices commonly used in the intensive care unit (ICU), like mechanical ventilators to help with breathing, central venous lines to deliver medicine or nutrients, and urinary catheters also increase the risk of infection.

Sepsis occurs when chemicals released into the bloodstream to fight infection trigger an inflammatory response. This in turn can damage internal organs, leading to multiorgan failure and critical illness or death. It’s therefore essential that doctors tending to trauma patients who have been moved into the ICU after initial resuscitation find ways to prevent, diagnose and treat the onset of bloodstream infections. Although antibiotic therapy is crucial for survival, it does not come without risks. A fundamental and unanswered question for many infections is that no one knows how long is best to treat.

“For patients who have sepsis, especially septic shock from infection, getting them on the right antibiotic early improves their outcomes. But we don’t know much about what to do after that, including how long to treat them,” says Dr. Nick Daneman, a scientist in the Tory Trauma Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) and an infectious disease specialist.

Over the past decade, clinical trials have found that shorter durations of antibiotic treatment are as effective as longer courses for syndromes caused by intra-abdominal infections, and those of the lung, skin, soft tissue and urinary tract. In one case, a landmark trial involving critically ill patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia found no differences in death and relapse rates among 402 patients who received antibiotics for eight versus 15 days.

Yet there are no studies that examine what duration of antibiotics is required for bloodstream infections. To address this void, Daneman and Dr. Rob Fowler, a senior scientist in the TECC Research Program at SRI and critical care doctor at Sunnybrook, established a research program called BALANCE, which stands for Bacteremia Antibiotic Length Actually Needed for Clinical Effectiveness.

The BALANCE program was developed to ask whether seven days of antibiotic therapy is as good as 14 days for preventing death among critically ill patients with bloodstream infections.

There’s another issue that is top of mind for Daneman and Fowler in doing this research. Audits show that 30% to 50% of antibiotic use in the ICU is inappropriate, says Daneman. Excessive antimicrobial use has led to rapidly rising antibiotic resistance rates. Daneman says the drugs can cause 5% to 10% of patients to experience side effects that include rash, gastrointestinal upset and diarrhea, kidney failure, hearing loss, dizziness and other adverse reactions. A more serious complication is C. difficile. The rate of this infection, which can cause diarrhea and life-threatening inflammation of the colon, has doubled in the past decade. About 5% of ICU patients with C. difficile will die.

“There is a global public health threat from antimicrobial resistance driven by antibiotic overuse and misuse in the context of a lack of new drug development,” says Daneman, who is a co-principal investigator of the BALANCE research program. “We need to work out how to best use available drugs to maximize benefits for patients, while minimizing harms for the patients themselves, neighbouring patients and future patients.”

Before launching the BALANCE trial, the researchers had to confirm the gaps in evidence and validate the urgent need to compare the length of antibiotic therapy for clinical effectiveness in patients with sepsis. The research team led five studies over five years leading to the current one. They did a systematic review of the medical literature, a national survey of Canadian infectious disease and critical care physicians, a single-centre retrospective study, a multicentre observational study and the BALANCE pilot randomized controlled trial. Findings from these studies laid the foundation for the BALANCE trial, a five-year, $2-million trial funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The analyses were done with support from the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (CCCTG), an organization comprised of more than 350 clinicians and researchers who work in ICUs across the country.

Dr. Rob Fowler (left) and Dr. Nick Daneman are leading studies to identify the right duration of antibiotics for patients in the ICU, who are at increased risk of getting sepsis.

“We were able to determine the BALANCE pilot study was feasible in terms of protocol adherence, site participation and interest,” says Asgar Rishu, project manager of the BALANCE research program. Patients in the BALANCE pilot study were from 15 hospital ICUs admitted for reasons deemed medical, surgical, traumatic, neurological or relating to burns. Sixty per cent of the infections were acquired in the community.

All 115 patients from the pilot study are enrolled in the current trial, which will recruit 3,600 patients. The BALANCE trial is randomizing critically ill patients with a bloodstream infection into two treatment arms—seven versus 14 days of antibiotics. The survival rate for each group will be measured at 90 days from the date bacteria is first detected in the bloodstream. Sunnybrook is leading the trial with 58 patients, and 206 patients are enrolled across all sites. Canada-wide, another 20 sites in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec are participating. The team has also engaged collaborators from Australia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland, Brazil, France, Israel and the United Kingdom.

“More and more people are realizing these large paradigm-setting trials need to be conducted across multiple countries,” says Daneman. “One, it helps with speed of recruitment to get to your target sample size. Two, it improves the generalizability of your findings when you can see if they are robust across different health care systems with different micro-organisms, different treatment practices.”

Fowler agrees. He says determining the differences among patients in a variety of countries might show a change in resistance patterns and rates of C. difficile. “We see certain antibiotic resistance patterns here that are worrisome, but then you go to other parts of the world and you realize this is an enormous problem. There are lots of places that are already in pretty tough shape with respect to not having drugs to treat infections.”

Knowledge gained from the BALANCE trial could lead to benefits for hospitalized patients and the health care system, as well as broad global reductions in antimicrobial use. “If shorter duration is as effective as longer duration therapy for these severe infections in the critically ill, findings may also reasonably be generalizable to non-bacteremic and non-critically ill populations, and hence could generate large reductions in hospital-wide antimicrobial consumption and complications,” says Rishu. As Daneman notes, uptake could be quick, “because it doesn’t require any new technology, doesn’t require any new expensive drugs, just a different way of deploying medications that we’re already using.”

“This research matters because it’s so fundamental to what we do as infectious disease specialists and antibiotic prescribers,” says Daneman. “We have to choose a drug and decide how long to use it for. We need to learn how to get those simple treatment decisions right, so we can maximize outcomes for the patients we are treating.”

In addition to changing practice and informing guidelines, the results could promote savings. “We anticipate that the costs associated just with the drugs would by definition be halved if you’re treating for seven versus 14 days,” says Fowler. “Then the associated side effects of C. difficile resistance or other organ injury that you might occasionally deal with antibiotics should favour fewer costs for the short-treatment arm.” He explains that unnecessarily prolonged antibiotic therapy contributes to an increase in ICU hospital stay by two to three weeks and excess costs to the health care system that range from $25,000 to $40,000.

Antibiotic resistance doesn’t happen overnight, Fowler says. “It’s the kind of thing that happens somewhat slowly, and like boiling water, you’re never really sure that you’re in trouble until you get beyond a certain point, and this is sort of one that has been boiling for quite a while.”

Intensive care needs intensive interaction

Clear and effective communication among health care professionals is paramount. New research shows there is a constant need to improve how medical teams interact and talk to each other to ensure quality care.

Few studies have looked at ways to improve communication between surgeons and critical care teams working in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a trauma centre. That prompted researchers at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) to examine the factors that lead to crossed wires between these teams day to day or when tough decisions need to be made.

“Understanding communication between clinicians is about understanding the relationships between clinicians, and their critical impact on the function of teams and on patient safety,” says Dr. Barbara Haas, a trauma surgeon, intensivist and health services researcher at SRI. “Without understanding the social context in which people work, we can't help them improve how they do it.”

Haas works with Dr. Lesley Gotlib Conn, a medical anthropologist at SRI. They led a study to probe the social and cultural context of surgical ICU work, and its implications for how surgery and intensive care teams interact to deliver care. Their findings highlight the challenges physicians face when it comes to delimiting their expertise, negotiating patient ownership and sharing decisional authority.

"We used anthropological research methods to explore communication as a proxy for team relationships and the culture of interspecialty care,” says Gotlib Conn. She conducted 50 hours of observations on routine patient care activity and 43 interviews with hospital staff.

Results showed that ensuring quality team-to-team communication is complex and, although it can be difficult, it can be improved. The researchers found surgeons and intensivists were eager to communicate more, but there were few facilitating structures. For example, the most valued form of communication was face-to-face conversation, but there were no routines to ensure this happened daily.

Although checklists and pagers are often used to facilitate communication, these tools can also impede it. “We have a pager system that should help people keep in touch. In reality, it often seems to lead to delays, ‘broken telephone’ and a lot of frustration,” says Haas. They also found that leaving notes by the bedside and changing the way staff record information did not help solve the challenges.

Surgeons, intensivists and nurses described episodes of poor communication, such as disputes over feeding or keeping a patient on a ventilator, as distressing—not only to them, but also to patients and the whole care team. Good communication was related to feelings of respect, trust and being valued. These findings reflect the need to foster an interspecialty team culture characterized by collaboration, equalized power relationships and mutual goals, says Gotlib Conn.

"It's critical that all doctors be on the same page," agrees Haas. As the trauma education lead, she encourages physicians, residents and interdisciplinary specialists to learn together and engage socially. “That way, when you’re meeting at three o’clock in the morning at the side of a patient’s bed, you know each other’s name, strengths and weaknesses,” says Haas. "We need to explore interventions that focus on building relationships and trust between teams that collaborate in taking care of complex patients.”

Identifying sepsis

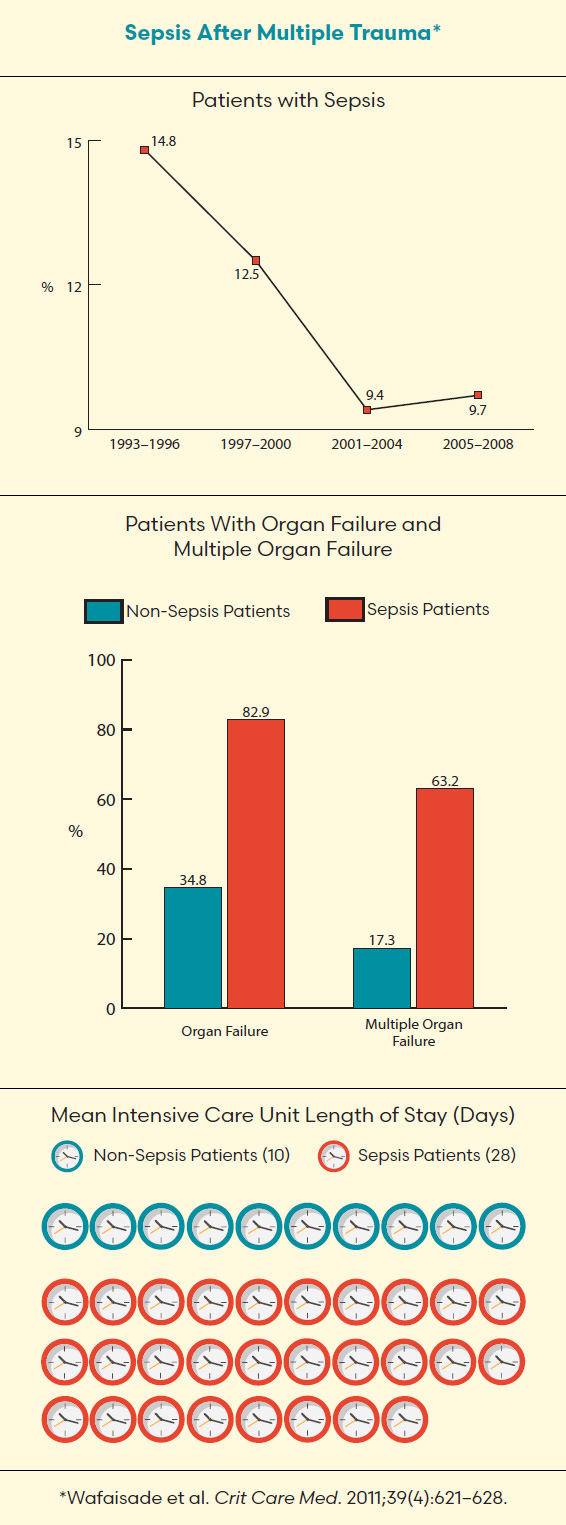

Dr. Gordon Rubenfeld says when people die after major trauma they usually do so in the first 48 hours. For those people who die from trauma outside that window, however, their deaths often are not from the trauma itself but from complications such as sepsis or the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In some cases, a combination of both illnesses presents in patients.

Rubenfeld, senior scientist in the Evaluative Clinical Sciences platform at Sunnybrook Research Institute and chief of the Tory Trauma Program at Sunnybrook, calls sepsis a “silent killer.” He defines it as “the body’s response to an infection” and says it occurs when the immune system engaged to fight off the infection becomes harmful. The complications can range in severity from a mild fever to multiple organ failure, also called multiple organ dysfunction, a life-threatening condition that affects at least two organs.

Occurring independently or in association with sepsis, ARDS is inflammation of the lungs. It is commonly caused by infection—usually pneumonia—but can also occur from trauma. Rubenfeld says when ARDS is a result of trauma it’s particularly problematic because patients are often put on ventilators, which places them at greater risk of infection.

Treating these potentially fatal complications is a matter of recognition and early management. For sepsis, rapidly administering antibiotics and intravenous fluids to offset dehydration is crucial, Rubenfeld says. If this seems straightforward, it’s because it is. Recognition and early management “were the mainstays of therapy 30 years ago, and they’re still the mainstays of therapy,” he says. Although the mortality rate associated with sepsis is declining, the challenge of accurately identifying the illness in a timely manner remains.

To tackle the obstacle, Rubenfeld, who is helping to write evidence-based guidelines for how to manage patients with sepsis, worked with a dozen other scientists to create qSOFA (quick sepsis related organ failure assessment). The tool is essentially a calculator that enables doctors and nurses to recognize patients with sepsis, or those soon to develop it, at an early stage. Low blood pressure, fast respiratory rate and altered mental status are three criteria that are evaluated to produce a score. This result is used to determine which patients need further testing and extra attention.

Rubenfeld says when treating ARDS the approach is, as with many aspects of modern trauma care, “less is more.” He adds that turning the dial down on ventilators and focusing on bedside teamwork and skill rather than high-tech treatments has been a significant advance. “Instead of taking a great big breath and putting it into an inflamed lung, we’ve learned to ventilate the lung gently,” he says. This change in therapy, paired with the idea of laying patients on their fronts and not their backs to open the base of the lung, has led to a decline in mortality rates.

While lower mortality rates among sepsis and ARDS patients is positive, Rubenfeld points to the aging population as a reason to increase awareness around the illnesses. An older population translates to an older trauma patient population, and aged trauma patients are at a greater risk of developing sepsis and ARDS complications. “The older population has made everything we’ve talked about in terms of sepsis and ARDS that much more important,” Rubenfeld says.

The BALANCE Research Program is funded by the AFP Innovation Fund at Sunnybrook through the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation, and the Physicians’ Services Foundation Incorporated.