No doubt

Doctorate student knows that the life he has fashioned—doing science, mentoring young people and preparing for a career in medicine—is his calling, but it wasn’t always that way

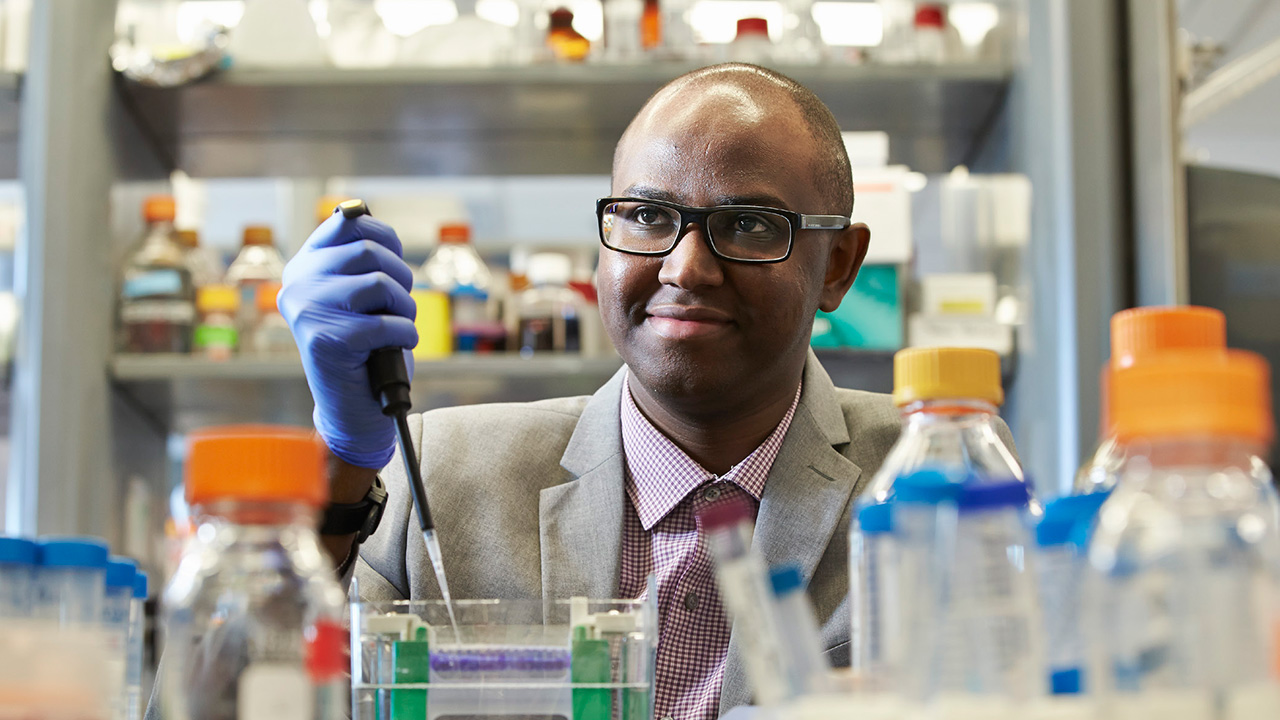

Abdikarim Abdullahi is a PhD student training in the lab of Sunnybrook Research Institute senior scientist Dr. Marc Jeschke.

Photo: Nation Wong

“If you’re lucky enough to do well, send the elevator down." So says Abdikarim Abdullahi in describing the motto he tries to live by. A third-year PhD student in the Institute of Medical Science at the University of Toronto, Abdullahi is training in the lab of Sunnybrook Research Institute senior scientist Dr. Marc Jeschke.

He’s usually at Sunnybrook until 11 p.m. on weeknights—“I’m more of a night person,” Abdullahi says—yet he finds time to tutor elementary school kids. On Saturdays, he works at a learning centre in the city’s west end instructing young kids in public speaking and science. Along with others, Abdullahi helped lead a team from the centre to national prominence in the First Lego League, a competition that encourages youth to get involved in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). He also mentors black university students pursuing graduate studies in research, where they are strikingly underrepresented. He founded a group where he and his colleagues help students of colour navigate graduate research programs. Offering guidance on matters like choosing a thesis advisory committee and applying for awards, Abdullahi gives the kind of support he wishes he’d had when he began his PhD. “I felt like I was the only one [in the program] who looked like this,” he says, recalling his first week of orientation. “I was kind of intimidated.”

Any doubts he had about whether he belonged in academia have dissipated. The 29-year-old, who is more than halfway through his doctoral studies, is flourishing. In 2016 he was awarded a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, one of the country’s most prestigious awards. The accolade, worth $150,000 over three years, recognizes academic excellence and leadership. Abdullahi, who has done extensive youth outreach for the city’s Somalian community, was ranked in the top 10th percentile of all applicants nation-wide.

He studies changes in metabolism in the liver and adipose (fat) tissue after a burn injury. His focus is on the biological mechanisms driving browning, a process by which the body shifts from storing to burning fat. Different types of fat get their name from the colour of the tissue, Abdullahi notes. White fat stores fat, whereas brown fat burns fat. He has found that the immune system plays a role in the metabolic changes that accompany browning. In preclinical models, Abdullahi showed that immune cells called macrophages secrete a protein called interleukin-6, which activates browning. On the other hand, “when you get rid of the ability of macrophages to get to the adipose tissue, [the mice] don’t brown,” says Abdullahi. In studies of mice that are engineered not to express the interleukin-6 gene, he has found that browning does not occur.

Abdullahi studies changes in metabolism in the liver and fat tissue after a burn injury. His focus is on a process called browning, where the body shifts from storing fat to burning fat.

Photo: Nation Wong

The topic is popular because controlling browning could benefit people who are obese or have diabetes. Abdullahi, however, is studying the dangers of this process in people who have burn injuries and cancer. In both conditions the body tailspins into a hypermetabolic state where it begins to waste away. As the body burns fat stores, it begins to ravage muscle tissue. He catalogued the harmful effects of browning ensuing from burns and cancer in a paper published in Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. The editors of the journal praised the research for its originality and featured the study on the cover of the August 2016 issue. “I actually have this framed,” says Abdullahi, pulling up a screenshot of the journal cover on his laptop.

This fall, he will continue his research into browning at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Maryland, under the guidance of Dr. Sheng Bi, a leading scholar in diabetes research. The catalyst for the placement was a travel award that Abdullahi won called the Michael Smith Foreign Study Supplement, which encourages outstanding Canadian graduate students to do research abroad and build global linkages. “I thought this was a great opportunity to expand my horizons,” says Abdullahi, noting he has his supervisor’s blessing. “When I told Marc he was pretty happy, too.”

He is excited about going to Johns Hopkins, but says that even though he is a Canadian citizen, he is wary of travelling to the U.S because he was born in Somalia. The political climate and the immigration ban drafted by the U.S. administration, which barred entry of people from six countries, including Somalia, weigh heavily on Abdullahi, even though the ban has been blocked by the courts. “I’m afraid especially now with Trump and ‘America First.’ They might think I’m going over there to work, even though I’m fully financed on a scholarship. I won’t be picking up jobs to finance myself. I’m going to make sure all that stuff is clear,” he says.

Abdullahi (left) tutors kids at the Academy for English and Mathematics in the city's west end.

Photo: Courtesy of Abdikarim Abdullahi

He is on track to graduate in two years. His plan is to attend medical school. His career goal is to become a clinician-scientist so that he can practise medicine and conduct discovery research that has clinical applications. “As a basic scientist you can get bogged down with the mice work and not understand how your data can be taken to the clinic, which is something I’m passionate about,” says Abdullahi. “You want that research to go somewhere.”

He is open about his aspirations now, but growing up in the Jane and Finch neighbourhood in Toronto, a diverse community that also has some of the highest rates of crime and gang violence in the city, he was reticent about his desire to pursue higher education. “I remember some of the guidance counselors weren’t supportive. They were more supportive of trades. I kept [my goals] to myself—then no one can shoot down your dreams,” says Abdullahi.The youngest of seven children, he is still considered the “baby” of the family, but Abdullahi is like an older brother to kids in the Jane and Finch community where he still lives. He goes back to his old schools to give young people a different message than the one he received and, perhaps, inspire them to pursue STEM. “It builds up their confidence,” he says of the visits. “They think, ‘maybe I can be like that one day.’”

Looking ahead, Abdullahi says that once he has his medical degree, he plans to live and work in Canada, and make regular trips to Somalia to provide pro bono health care. He says he often thinks about how different his life would have been had his parents not immigrated here. It is these thoughts that push him to excel academically and to pay his blessings forward. “Whenever I accomplish something, I want to give back. You have to take every opportunity you get and run with it.”

— Alisa Kim