Are recent immigrants to Ontario healthy?

Data dig unearths unexpected findings

June 13, 2016

Shortly after he was elected, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau gave a speech in London, U.K. on Canada’s response to the Syrian refugee crisis. He spoke behind a podium bearing the sign “Diversity is Canada’s strength.” With one of the highest per capita immigration rates among wealthy countries, Canada is a diverse nation, with roughly 250,000 immigrants arriving each year. Yet we know surprisingly little about the health of these immigrants after they settle in.

For Dr. Jack Tu, the desire to learn more about how settlers fare in their new country comes from his own story. He and his parents left Taiwan and moved to Canada when he was one year old. “As an immigrant myself, I’ve always been interested in cardiovascular health in different immigrant groups,” he says. “Historically, there’s relatively little data on this topic.”

Tu is a cardiologist and senior scientist at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI). He leads the Cardiovascular Health in Ambulatory Care Research Team (CANHEART) at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). He was the first author of the CANHEART Immigration Study, which looked at the incidence of major cardiovascular events like heart attack or stroke in immigrants to Ontario. A research agreement between Citizenship and Immigration Canada and ICES gave him access to the government’s permanent resident database. By linking those data to the health databases at ICES, Tu and his team could look for differences between immigrant and non-immigrant populations.

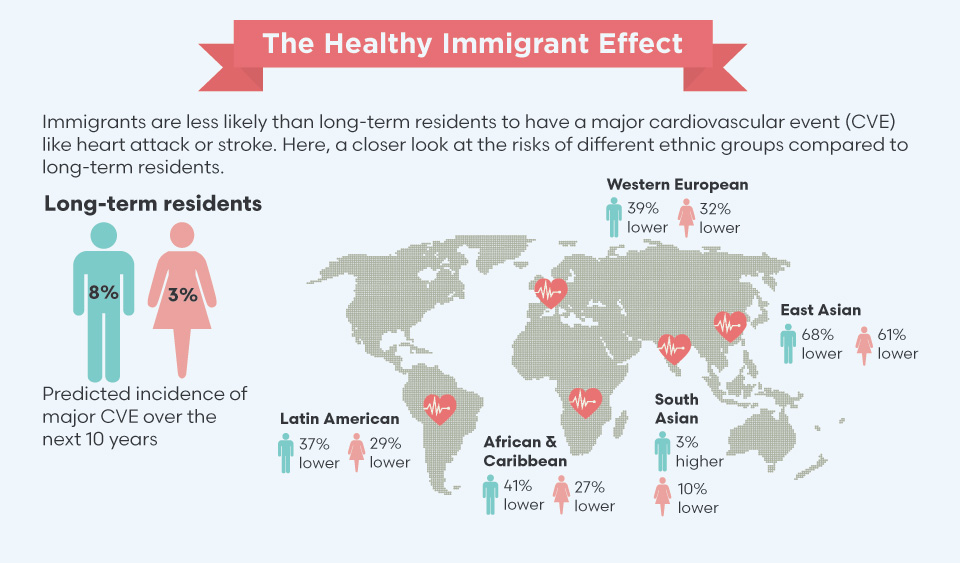

What they discovered was surprising. “Most studies in Europe show immigrants there do worse than people born in Europe, but we found the opposite with immigrants here,” says Tu. Major cardiovascular events occurred 30% less often in newcomers than in long-term residents. This so-called “healthy immigrant” effect is partly explained by a lower cardiac risk factor score for newcomers, which takes into account things like diabetes, hypertension, cholesterol level and smoking status.

Dr. Jack Tu is using large databases to study the effect of immigration status on heart health.

Within the immigrant population, the researchers found startling differences between ethnic groups. For example, the incidence of major cardiovascular events was nearly four times higher in South Asian immigrants—those from Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka—than in East Asian immigrants from China and Korea, who had the lowest overall incidence. Tu puts his results into perspective. “If you’re a smoker or diabetic, or [have] high blood pressure, that doubles your risk,” he says. “If you’re a South Asian compared to an East Asian, that quadruples your risk.” For some immigrant groups, where you come from puts you at greater risk for heart problems than smoking or being obese.

As for why immigrants to Canada seem to be healthier than their European counterparts, Tu says there are two main reasons. The first is Canada’s rigorous screening process, which includes extensive health requirements. This means that newcomers to Canada are likely healthier at the outset than those in Europe, whose porous borders allow easier entry and movement of people from one country to another. The second reason is Canada’s universal health care system, which ensures that all residents have access to preventive care.

“For the first time, we know the incidence of [cardiovascular] events for the different groups in Canada,” says Tu. Using this knowledge, he and his team are building better prediction models that incorporate ethnicity to assess cardiac risk. The currently used Framingham risk score was developed based on a predominantly Caucasian population, which is “potentially misleading for people from other ethnic groups,” he says.

While the CANHEART Immigration Study found that newcomers had better heart health and were less likely to have a heart attack or stroke, it did not provide insight into how well they do after suffering a major health setback. Specifically, how did their survival rates compare to those of long-term residents?

That’s the question that prompted Drs. Matthew Cheung and Simron Singh to study the impact of immigration status on cancer outcomes. Using the same databases as Tu, they looked at mortality rates in immigrant and non-immigrant populations between 2000 and 2012 in Ontario. Their analysis controlled for factors that might influence cancer mortality, like age, type of cancer and stage at diagnosis. “We found that there was a considerable reduction in mortality in individuals who had immigrated to Canada,” says Cheung, who is an associate scientist at SRI and a blood specialist at Sunnybrook’s Odette Cancer Centre. Recent settlers—those arriving within the last 10 years—were 14% less likely to die from cancer than non-immigrants. For immigrants who had been in the country for 11 to 25 years, their odds of dying from cancer were 9% lower than non-immigrants. “They seem to have some sort of advantage in terms of both cancer-related survival as well as overall survival,” he says.

“We weren’t expecting to find this ‘healthy immigrant’ effect in cancer,” agrees Singh, a medical oncologist and affiliate scientist at SRI and ICES. “We were very worried when we did this study that we would find results that show immigrants did worse.” The researchers feared that unfamiliarity with the health care system would hinder newcomers from accessing the care they needed. “We were, in a way, pleasantly surprised that Canada’s public health care system works. It works for people who are new to the country. It works for people regardless of socioeconomic status and colour of their skin.”

The researchers also found that immigrants’ survival advantage decreased with time, possibly owing to lifestyle changes in their new home. The longer they stayed in Canada, the closer their survival rates were to the non-immigrant population. As the next step, Cheung and Singh are taking a closer look at specific cancers and how survival rates differ between the two groups. They are also trying to identify factors that contribute to the healthy immigrant effect in hopes of using those traits to help all cancer patients better their odds.

As the researchers note, this study was the first to find a consistent link between immigration status and reduced cancer-specific mortality. It contrasts with American studies, which showed that immigrants to the U.S. typically do worse than U.S.-born people. The researchers note that Canada’s public health care system is likely responsible for the improved outcomes seen in our immigrant population. “I want people to have confidence in the Canadian health care system,” says Singh. “[This was] a study on the cancer system, and the system gets a passing grade from us.”

Source: Tu JV et al. Circulation. 2015;132:1549–59.

Cheung and Singh’s research is funded by the Canadian Cancer Society, and Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Tu’s research is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and Public Health Agency of Canada.