Beyond World Cancer Day: advancing research into predictive, personalized and precise cancer treatment

A new kind of MRI to predict response to cancer therapy

How a person with cancer will respond to a treatment is near impossible for doctors to know. One aspect of a tumour that may shed light on this question is the way in which it processes energy sources.

How a person with cancer will respond to a treatment is near impossible for doctors to know. One aspect of a tumour that may shed light on this question is the way in which it processes energy sources.

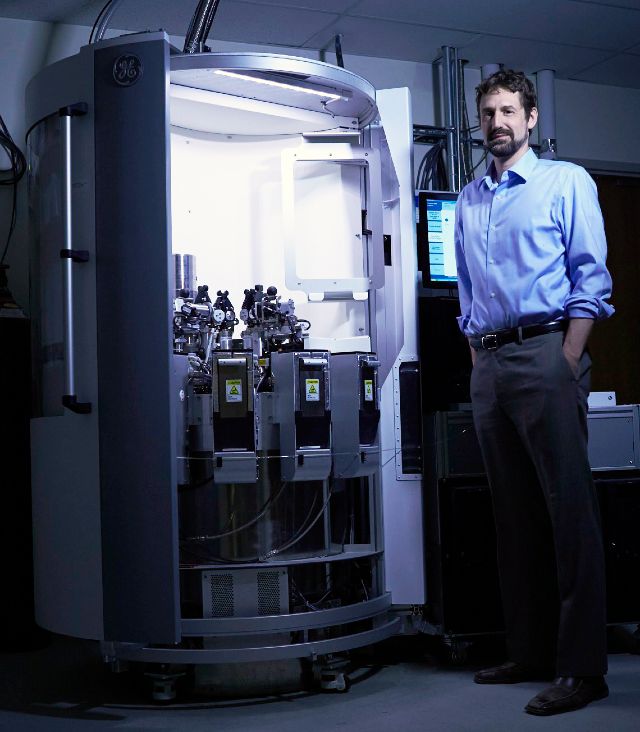

Dr. Charles Cunningham, a senior scientist in Physical Sciences at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI), is developing an imaging tool that could help oncologists understand a tumour’s metabolism—all the chemical processes that take place in a tumour—and its relationship to treatment.

He is studying a method using MRI that allows researchers to look at chemical processes in the body safely and noninvasively. To do this, he is using a contrast agent, a kind of dye that helps doctors see inside the body, made of pyruvate, a molecule that’s produced when cells use glucose for energy. The contrast agent is prepared in such a way that it enhances signals from MRI, and then is injected into a person undergoing MRI. This then enables doctors to look at biochemical reactions within tissue as cells metabolize, or take up, the contrast agent.

Cunningham is working with oncologists at Sunnybrook to study how the imaging technique can be used to learn about tumour metabolism, and if it can predict therapy response and help personalize a patient’s treatment. He is leading five clinical trials at Sunnybrook studying hyperpolarized MRI in various types of cancer, including prostate cancer, cancer that has spread to the brain, locally advanced breast cancer and locally advanced cervical cancer.

Sunnybrook Research Institute has the only clinical hyperpolarizer in Canada. In 2016, Cunningham and colleagues became the first in the world to demonstrate noninvasive metabolic MRI of the human heart.

New ultrasound method for breast cancer can detect treatment response early and screen for cancer better

It can take months for oncologists to determine whether a tumour is responding to chemotherapy, a wait that is far too long.

It can take months for oncologists to determine whether a tumour is responding to chemotherapy, a wait that is far too long.

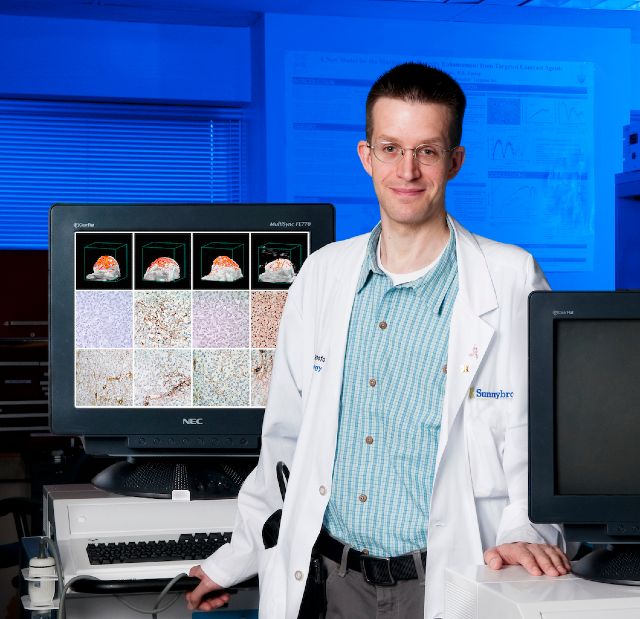

Dr. Greg Czarnota, director of the Odette Cancer Research Program at SRI, has developed an imaging technique that can show a person’s response to cancer treatment much sooner. The method uses raw data produced by ultrasound machines to detect whether tumour cells are dying. In a study of 100 women with an aggressive form of breast cancer, Czarnota and colleagues showed they could predict tumour response with 82% accuracy using the technique after just one week of chemotherapy. The aim is to translate the technology into the clinic, so that oncologists can personalize care through early therapy response monitoring.

He is also studying use of this technique in women with suspicious breast lesions for rapid diagnosis of breast cancer. In an early study, Czarnota and colleagues showed that by analyzing features of the ultrasound signal, they could distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. The technique has the potential to provide a diagnosis on the spot, as opposed to what happens now, where women wait up to one month to find out if a breast lump is cancerous, which can be the case if a biopsy is needed.

Tackling a different problem—that of the debilitating pain caused by cancer that has spread to bone— Czarnota is examining the effectiveness of a noninvasive technology called focused ultrasound to reduce this pain. In a pilot study, he found that five out of six patients reported feeling less pain and had no adverse effects 30 days after focused ultrasound treatment.

Maximizing quality of care and quality of life for people with cancers of the liver, pancreas and bile ducts

Improving outcomes and quality of life for people with cancers of the liver, pancreas and bile ducts is a main focus of the research of Dr. Julie Hallet, a surgeon-scientist at SRI.

Improving outcomes and quality of life for people with cancers of the liver, pancreas and bile ducts is a main focus of the research of Dr. Julie Hallet, a surgeon-scientist at SRI.

For patients that do not live in cities with specialized cancer centres, where expert surgical care is often provided, travelling to receive post-surgery treatment can be stressful. Hallet, with colleagues at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, recently led a study comparing patients with pancreatic cancer who had received chemotherapy at the same centre where they had their surgery to patients who received their chemotherapy at a different hospital after surgery. When they analyzed the data from these 589 patients, they found that there was no difference in overall survival between the two groups. Patients who had their chemotherapy at a different hospital travelled about 23 km. The average travel distance was more than 106 km to the centre where the surgery was done. The results suggest that pancreatic cancer patients’ travel burden can be reduced without compromising their quality of care.

Hallet has also done research to minimize complications from cancer treatment. She led a large study highlighting the risks of blood transfusions during surgery to remove liver tumours arising from colorectal cancer. It focused on 483 people who had the operation at Sunnybrook between 2003 and 2012. People who had a transfusion during or right after surgery had a survival rate that was 15% lower than that of people who didn’t have one.

World-first trials of focused ultrasound to treat cancers of the brain, head and neck, and rectum

Tumours originating in the brain can be difficult, and sometimes impossible, to treat. Drugs are ineffective because the blood-brain barrier blocks almost all of them from reaching the brain. Surgery is invasive and carries risks of complications. Focused ultrasound might be a way to get around these challenges.

Tumours originating in the brain can be difficult, and sometimes impossible, to treat. Drugs are ineffective because the blood-brain barrier blocks almost all of them from reaching the brain. Surgery is invasive and carries risks of complications. Focused ultrasound might be a way to get around these challenges.

Dr. Kullervo Hynynen, director of Physical Sciences, and Sunnybrook neurosurgeon Dr. Todd Mainprize launched a trial in 2015 that was the first in the world to use low-intensity focused ultrasound to breach the blood-brain barrier and deliver chemotherapy into the brains of patients with brain cancer. The study’s results, published in January 2019 in Scientific Reports, showed that MRI-guided focused ultrasound can disrupt the barrier safely and effectively to allow chemotherapy drugs to enter the brain.

Now, Dr. Nir Lipsman has launched a study where people with glioblastoma who have already had surgery will be treated with focused ultrasound, along with the current standard of care maintenance chemotherapy.

Further, Mainprize is leading a study looking at using focused ultrasound at a higher intensity, as a kind of scalpel-free surgery, to heat and destroy primary brain tumours, and tumours that have spread to the brain from elsewhere.

Hynynen, who is credited with pioneering focused ultrasound technology, is also leading the world’s first trial of MRI-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound to treat head and neck cancer, the sixth most common form of cancer. Despite treatment, between 20% and 55% of people with advanced head and neck cancer will experience recurrence of disease. In the study, patients with head and neck cancer receive MRI-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound in addition to standard chemotherapy and palliative radiotherapy. The goal of this early-stage study is to assess the safety, toxicity and feasibility of focused ultrasound. The ultimate goal is to determine if focused ultrasound might make treatment more effective.

Hynynen and Dr. William Chu, a radiation oncologist at Sunnybrook and researcher at SRI, are conducting the world’s first clinical trial on the use of MRI-guided focused ultrasound to treat recurrent rectal cancer. In people in whom the disease returns, standard treatments do not work well. Hynynen and Chu are testing whether thermal treatment of cancer using focused ultrasound can be used safely with radiation and chemotherapy without increased negative side effects.

A noninvasive test for bespoke prostate cancer care

Men with early prostate cancer can either treat the disease aggressively or monitor it through active surveillance, also called “watchful waiting.” Each option has risks and benefits. It is hard to distinguish men that can be watched from those whose disease is more dangerous and thus require vigorous treatment.

Men with early prostate cancer can either treat the disease aggressively or monitor it through active surveillance, also called “watchful waiting.” Each option has risks and benefits. It is hard to distinguish men that can be watched from those whose disease is more dangerous and thus require vigorous treatment.

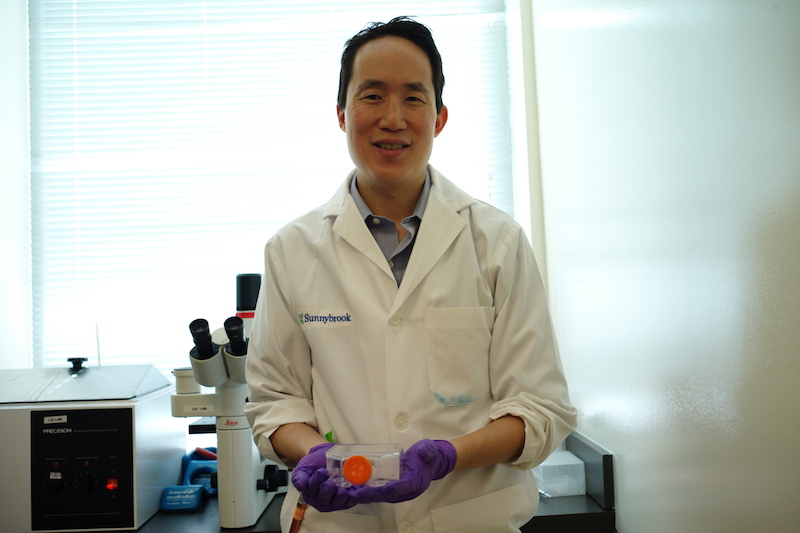

Dr. Stanley Liu, a scientist in the Odette Cancer Research Program and radiation oncologist at Sunnybrook, is developing a noninvasive test to help guide prostate cancer management. The aim is to identify urinary biomarkers—measurable substances in the body, like proteins, that can indicate if tissue is healthy or diseased— so that doctors can determine upfront which men with early prostate cancer are more likely to need surgery or radiation, as opposed to active surveillance. This personalized approach will improve long-term survival and quality of life of men diagnosed with the disease.

“Training” a computer to predict a breast cancer’s return

Before deciding upon a course of treatment, it would be ideal to know how likely it is that the cancer will return, something that is impossible to know now.

Before deciding upon a course of treatment, it would be ideal to know how likely it is that the cancer will return, something that is impossible to know now.

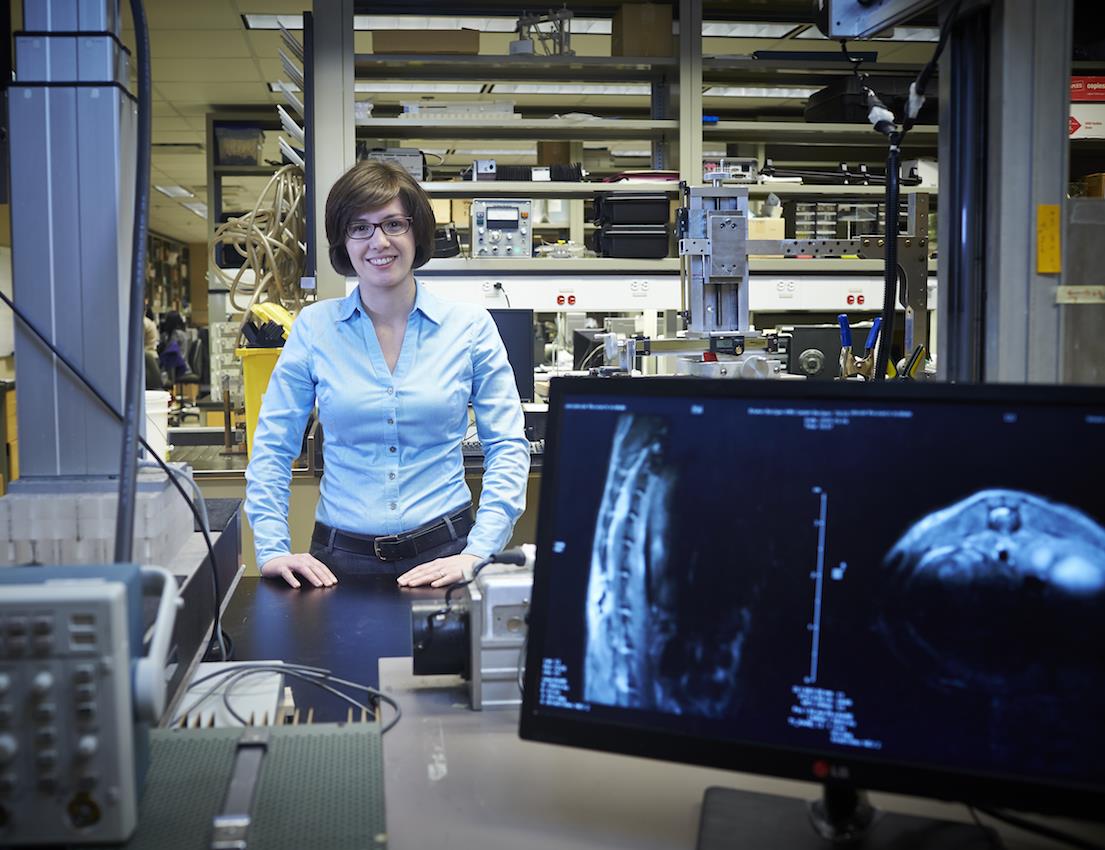

Dr. Anne Martel, a senior scientist in Physical Sciences, is using machine-learning techniques to predict breast cancer recurrence. She is developing a tool that uses imaging data to “learn” features of aggressive disease toward identifying low- and high-risk cancers. The aim is to help oncologists provide care that is individualized so that a woman can avoid taking toxic chemotherapy drugs if she doesn’t need to do without affecting survival, for example.

Using focused ultrasound to treat cancer in the spinal cord

The brain and spinal cord have barriers made up of blood and cells that protect the central nervous system from toxins. These barriers also prevent drugs from reaching their target, however, which makes treating these diseases challenging.

The brain and spinal cord have barriers made up of blood and cells that protect the central nervous system from toxins. These barriers also prevent drugs from reaching their target, however, which makes treating these diseases challenging.

Dr. Meaghan O’Reilly, a scientist in Physical Sciences is studying the use of a noninvasive technology pioneered at Sunnybrook Research Institute called focused ultrasound to open the blood-spinal cord barrier and deliver drugs to treat spinal cord tumours. In one study on preclinical models, but using human tumours, she showed that the technique resulted in significant shrinkage of spinal cord tumours without negative side effects. The aim of this research is to give people with spinal cord disease a noninvasive treatment option.

Unleashing the immune system to fight melanoma and other cancers

The incidence of melanoma, an aggressive skin cancer, has more than tripled in the last 30 years. In 2017, melanoma accounted for about 1,250 deaths in North America.

The incidence of melanoma, an aggressive skin cancer, has more than tripled in the last 30 years. In 2017, melanoma accounted for about 1,250 deaths in North America.

Dr. Juan Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker, a senior scientist in Biological Sciences, has discovered a new tool to combat the deadly disease. He showed that a type of immune cell called gamma delta T cell could be produced from human stem cells to identify and destroy antigens—foreign invaders in the body—associated with melanoma tumours. Being able to generate these T cells in the lab to give to patients with cancer is now on the horizon as a therapeutic aim.

The finding is also a new principle of basic biology—one that will lead to the rewriting of immunology textbooks—as it was previously held that only another kind of cell, the alpha beta T cell, could kill tumour-associated antigens. Moreover, although the first study was done in melanoma, the finding has implications for other cancers, too.