Gut reaction

The trillions of microorganisms that call our bodies home are essential to our well-being. Bacteria in the gut, for example, help us to digest food that we couldn’t otherwise break down. Moreover, gut microbes—referred to as commensals (from com—‘sharing’ and mensa—‘a table’) because they share our diet and reside on us harmlessly—stimulate the development of the immune system.

On the flip side, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease and diabetes, among other conditions, are linked to the makeup of the gut microbiome, notes Dr. Philippe Poussier, a senior scientist in Biological Sciences at Sunnybrook Research Institute. The gut microbiome is made up of the bacteria in the digestive tract and their genes. For Poussier, who is interested in the factors that increase the risk of Type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disorder, looking at immune responses to the gut microbiome is a good starting point.

He and Dr. Jayne Danska, a senior scientist at SickKids Hospital in Toronto, Canada, are the first to show a connection between immune responses to gut bacteria and future development of Type 1 diabetes. The study was published in Science Immunology on Feb. 1, 2019.

The researchers studied two groups: healthy children with genes that contribute to a higher risk of developing Type 1 diabetes, and healthy prediabetic children with the same genes. The prediabetic kids had normal blood sugar levels and had not been diagnosed with diabetes, but had antibodies to the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas called islet beta cells, a feature indicative of ongoing destruction of these cells. Antibodies are proteins normally made by the immune system when it detects a harmful substance like a virus.

The research team assessed the levels of blood antibodies to commensal gut bacteria in children from each group, and found differences in immune responses to these microbes that were strongly associated with a future diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes.

The finding is critical. Prior to the study, the only predictive marker for Type 1 diabetes was the presence of antibodies to islet beta cells. “The results of our study show that there’s another biomarker: how people respond to commensal bacteria. They also suggest that the interaction between the immune system and the intestinal microbiome is a contributing factor to the development of the disease,” says Poussier, who is also an associate professor of immunology at the University of Toronto.

In their initial experiments, the team compared the two groups’ immune responses to intestinal flora without matching them for the Type 1 diabetes susceptibility genes. They found no differences. “Once we had made sure that these individuals carried the same genetic susceptibility to Type 1 diabetes, we could detect a difference. Why they ended up responding differently to commensal bacteria—depending on whether they were going to develop diabetes or not—that we still don’t know,” he says.

Also not known is what triggers the destruction of islet beta cells by the immune system of people with Type 1 diabetes. Insulin is an essential hormone that moves the sugar from the blood into the cells of the body for energy. Chronically high blood sugar can damage nerves, blood vessels, the kidneys and eyes, and it increases the risk of heart disease and stroke.

People with Type 1 diabetes must inject insulin daily because they can’t make enough of it on their own. Otherwise, in the absence of glucose, their cells seek out an alternate energy source—fat—resulting in the blood becoming acidic. This condition is called ketoacidosis [kee-toe-a-sid-oh-sis]; untreated, it can lead to coma and death. In Canada, more than 300,000 people live with Type 1 diabetes.

The researchers began their study by looking for differences in immune responses to gut bacteria among healthy children and kids with Crohn’s disease, another autoimmune disorder. In Crohn’s, the immune system mistakes friendly bugs in the intestines for foreign invaders, leading to inflammation and damage to the digestive tract.

They found that those with Crohn’s disease had higher levels of antibodies to the bacteria than did the healthy children. Poussier says this finding is unsurprising. “You have inflammation of the gut and damage to the gut barrier. Consequently, you have increased exposure to the bugs in your [intestine] and, sure enough, increased antibody response,” he says.

The team also compared antibody responses to gut microbes in children recently diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes and healthy children of the same age. Differences in patterns of antibody responses to the bacteria between the two groups emerged. “We were concerned that these differences could be a consequence of the metabolic imbalance of diabetic children,” says Poussier. “This is the reason why we decided to study immune responses of the children long before some of them developed the disease.”

Poussier is keen on learning if differences in the way the immune system “sees” harmless bacteria can be observed before an autoimmune response kicks in. He has yet to plan studies looking at this, but he envisions the usefulness of the biomarker long before there are signs that Type 1 diabetes is on the horizon. “Can you detect this before autoantibodies [to islet beta cells] become detectable? Let’s imagine that one day there is a way to prevent the disease—you would like to [diagnose] it as early as possible, prior to the process having destroyed a lot of insulin-producing cells.”

Read text-only version of above infographic

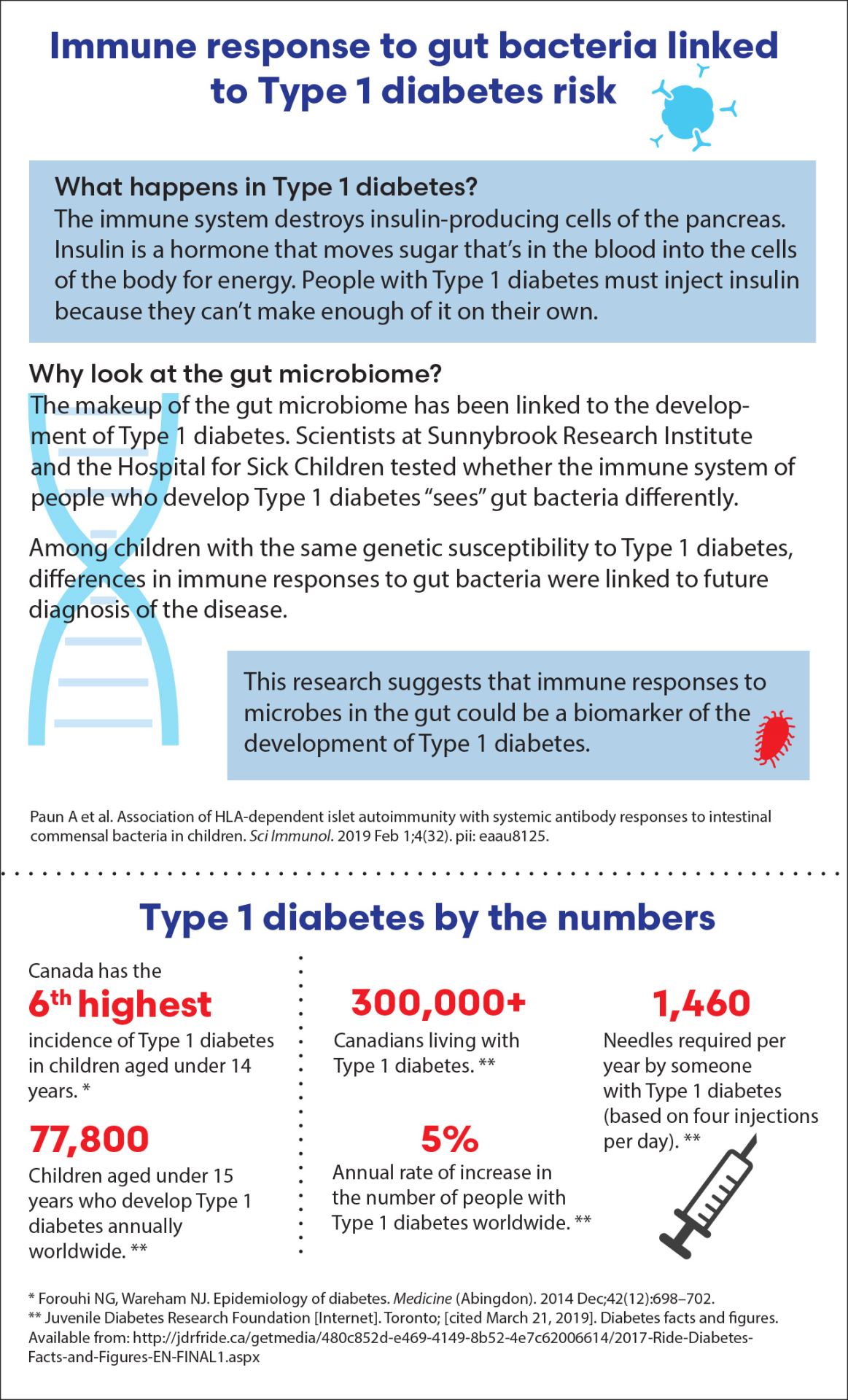

Immune response to gut bacteria linked to Type 1 diabetes risk

What happens in Type 1 diabetes?

The immune system destroys insulin-producing cells of the pancreas. Insulin is a hormone that moves sugar that’s in the blood into the cells of the body for energy. People with Type 1 diabetes must inject insulin because they can’t make enough of it on their own.

Why look at the gut microbiome?

The makeup of the gut microbiome has been linked to the development of Type 1 diabetes. Scientists at Sunnybrook Research Institute and the Hospital for Sick Children tested whether the immune system of people who develop Type 1 diabetes “sees” gut bacteria differently.

Among children with the same genetic susceptibility to Type 1 diabetes, differences in immune responses to gut bacteria were linked to future diagnosis of the disease.

This research suggests that immune responses to microbes in the gut could be a biomarker of the development of Type 1 diabetes.

Source: Paun A et al. Association of HLA-dependent islet autoimmunity with systemic antibody responses to intestinal commensal bacteria in children. Sci Immunol. 2019 Feb 1;4(32). pii: eaau8125.

Type 1 diabetes by the numbers

- Canada has the 6th highest incidence of Type 1 diabetes in children aged under 14 years. *

- 77,800: Children aged under 15 years who develop Type 1 diabetes annually worldwide. **

- 300,000+: Canadians living with Type 1 diabetes. **

- 5%: The immune system destroys insulin-producing cells of the pancreas.

- 1,460: Needles required per year by someone with Type 1 diabetes (based on four injections per day). **

Sources:

* Forouhi NG, Wareham NJ. Epidemiology of diabetes. Medicine (Abingdon). 2014 Dec;42(12):698–702.

** Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation [Internet]. Toronto; [cited March 21, 2019]. Diabetes facts and figures. Available from: http://jdrfride.ca/getmedia/480c852d-e469-4149-8b52-4e7c62006614/2017-Ride-Diabetes- Facts-and-Figures-EN-FINAL1.aspx

Original article: Paun A, Yau C, Meshkibaf S, Daigneault MC, Marandi L, Mortin-Toth S, Bar-Or A, Allen-Vercoe E, Poussier P, Danska JS. Association of HLA-dependent islet autoimmunity with systemic antibody responses to intestinal commensal bacteria in children. Sci Immunol. 2019 Feb 1;4(32). pii: eaau8125. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aau8125.

In a nutshell

- Dr. Philippe Poussier is co-senior author of a study published in Science Immunology looking at the link between immune responses to gut bacteria in Type 1 diabetes.

- The researchers showed that among kids with the same genetic susceptibility to Type 1 diabetes, differences in immune responses to gut bacteria were strongly linked to future diagnosis of the disease.

- It is the first study to relate differences in the way the immune system “sees” gut bacteria and future development of Type 1 diabetes.