Stomach cancer surgical practices and outcomes vary regionally: study

Ask someone what Napoléon Bonaparte, Liz Claiborne, Frank Mozart, Fred Rogers and John Wayne have in common, and their reply will likely revolve around fame. Accurate as that response is, there’s another link among these standouts: they all had gastric cancer.

Otherwise known as stomach cancer, gastric cancer, which was the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. until the 1930s, is a more uncommon form of cancer in North America today. In 2017, an estimated 2,100 people in Canada died from it. Compare it to breast cancer, which claimed the lives of 5,000 women in Canada in 2017, and its rarity comes into focus. With 3,500 Canadian diagnoses in 2017, its incidence is relatively low; however, that doesn’t dissuade Dr. Natalie Coburn, an associate scientist in the Odette Cancer Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI), from studying it.

“Something like breast cancer gets a ton of money because it’s a very common disease, but the chance of dying from breast cancer is much less than the chance of dying from gastric cancer,” says Coburn, who is also a surgical oncologist at Sunnybrook and an associate professor in the department of surgery at the University of Toronto. Lack of screening programs for gastric cancer in North America means that when people do present with the disease, it’s often late-stage and difficult to treat.

One of Coburn’s latest research efforts is centred on establishing a benchmark for gastric cancer care in Ontario. Published in Current Oncology, the main finding was that, similar to the U.S., there is variation. “I think how we’re doing, as a province, is in line with [how] most of North America is doing. We see variation because it’s a rare disease, but I certainly think we can do better,” she says.

To investigate gastric cancer care in Ontario, Coburn and her team invited an international panel of experts to Toronto, Ont., where they defined standards of care. Once that was done, Coburn and her group, which included Dr. Alyson Mahar at the University of Manitoba, set out to determine how Ontario is faring. They collected and evaluated data on 722 gastric cancer patients in the province who had gastrectomies between April 2005 and March 2008.

A gastrectomy is a surgery in which a patient has either part of their stomach—that which contains a cancerous tumour—or their entire stomach and some surrounding organs removed. To replace the stomach when it has been taken out, the evidence suggests the best solution is for specialists to construct a pouch and attach it to the esophagus, Coburn says.

“Compared to the U.S., our survival curves look really quite reasonable. The quality of care provided in Ontario is on par with North America, if not better, but overall, areas can be improved,” Coburn says.

Too much variability in surgical practices

One weakness she points to is the number of lymph nodes assessed. Examining lymph nodes allows doctors to ascertain the extent to which cancer has spread. In this study, the median number analyzed was 14. (The median value is the midpoint of a range of values, meaning that one-half of the values fell below this point, and one-half fell above it.) How many lymph nodes were assessed varied regionally. Coburn says at least 16 lymph nodes should be examined, based on international systems that are used to identify the stage of a person’s cancer. The highest performing region met this metric in about 74% of cases, while the lowest performing region achieved the goal in about 42% of cases.

Another area for improvement is the rate of in-hospital death following gastrectomy. Coburn found that it ranged from 0% to about 17% in Ontario, with the average at about 5%. She notes that Cancer Care Ontario’s (CCO) target is less than 5%.

Efforts should also focus on decreasing the rate of positive surgical margins, she says. This refers to the existence of cancer cells at the edge of removed tissue, and usually means more surgery is needed because cancer cells, which are too small to be seen, may still remain. Coburn says CCO strives for a rate of less than 5%. In her study, she found the average positive surgical margin rate to be about 28%, ranging from 15% to 50%.

These findings emphasize the differences in treatment across Ontario and the need to standardize care to improve results, Coburn says. “No one [centre] is doing as good a job as it could be doing,” she adds. Given the variation within the province, Coburn also stresses how important it is for patients to inquire about their care team’s expertise. “If you’re a patient, you want to talk to your care providers and ask them, ‘How much experience do you have with this surgery or with this type of chemotherapy or with this radiation modality?’ Not every team has the same level of expertise,” she says. “If you have a rare disease, you should find a team that has experience treating it.”

Conducting a study like this is no easy task. “Getting this type of information is difficult here in Ontario, because everything isn’t centrally linked, and the things that are centrally linked are not actually available for research—they’re only available for clinical care.” She details how a team member had to visit every hospital in Ontario, locate the medical records department and then rifle through countless paper charts to extract the relevant data. “It took a tremendous amount of work and was a huge undertaking,” Coburn says.

Competition between centres spurs improvement

Armed with the results from her study, Coburn approached CCO before publishing her findings and highlighted where variation in care exists. The organization followed up by doing similar research over more recent years, compiling the information and releasing a report to all centres in the province. “Most teams don’t know where they stand with a rare disease like [gastric cancer],” Coburn says. By distributing a report that shows where centres rank in comparison to each other, there’s a firm push to improve care.

“Most surgeons and most physicians are competitive people. If you hand them a report that says, ‘Here are the results,’ and your centre is mid-pack or at the bottom, you would expect in the coming years that it’ll get better. Even if you’re at the top of the list, it’s tough to stay there, so you’ll start doing more,” she says. “That improves care for everybody. It’s important.”

Speaking about CCO’s recent results, Coburn says there is still variation, but there is less now than there was when she investigated cases from over a decade ago. The hope is that each new study will show a decline in variation and an improvement in patient outcomes.

Learning from leaders, connecting with patients

The focus now is on standardizing care. To this end, Coburn invited stomach surgeons from South Korea, Japan and the U.S. to Sunnybrook in June 2018. South Korea and Japan are lauded as exemplars in the field of gastric cancer care, mostly because the incidence in those countries is exceedingly high, so doctors there perform many gastrectomies. The incidence per 100,000 people in South Korea and Japan is about 40 and 28, respectively, compared to four in Canada.

During the gathering, surgical techniques were discussed, and it became apparent that even among the best in the world, there is variation. The take-home message was that, by exchanging experiences, every participant can learn.

Coburn hopes to build on this in the coming years. “There are many ways to do a surgery, and there are subtle variations. Whether those variations have any impact on how the patients do is hard to know, but it’s probably better to get everyone on the same page, to get patients on the same pathway,” she says.

To do this, Coburn and her team developed a website with patients in mind. The aim is to deliver accurate information about gastric cancer and the treatment options available, as there is an abundance of falsity online. “We tried to write it in language that’s easier for patients to understand. Giving patients this information empowers them to make the right choices,” Coburn says. Links to publications and clinical trials are included.

Coburn plans to continue exploring gastric cancer care, zeroing in on how patients navigate through the system and whether services are provided to them when needed. Asked what gives her fuel to do her research, there’s no pause before she says, “The patients I see in the clinic. You always know you can do better. Every hospital knows it can do better if it pushes itself a little bit harder.”

Read text-only version of above infographic

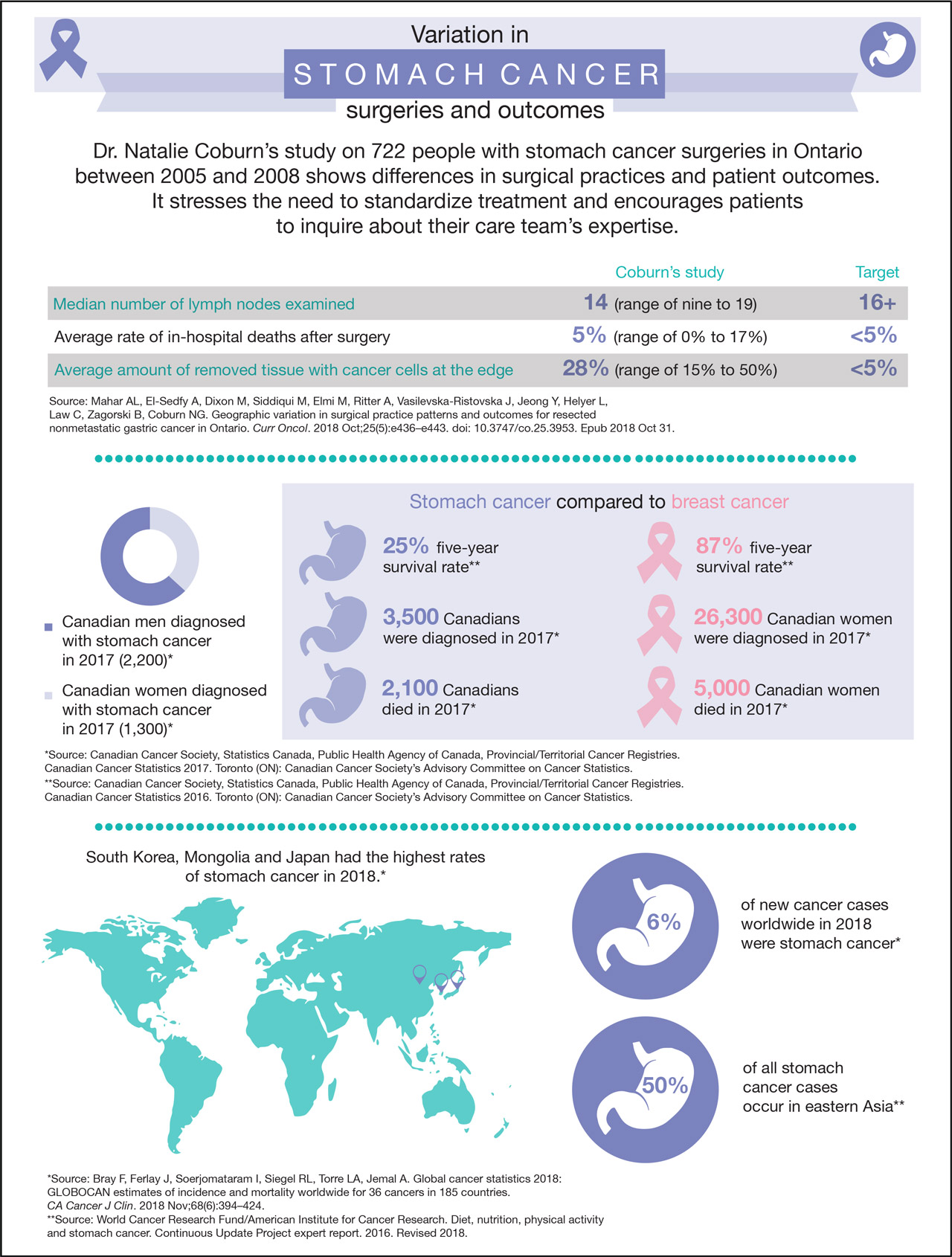

Variation in stomach cancer surgeries and outcomes

Dr. Natalie Coburn’s study on 722 people with stomach cancer surgeries in Ontario between 2005 and 2008 shows differences in surgical practices and patient outcomes. It stresses the need to standardize treatment and encourages patients to inquire about their care team’s expertise.

Median number of lymph nodes examined

Coburn’s study: 14 (range of nine to 19)

Target: 16+

Average rate of in-hospital deaths after surgery

Coburn’s study: 5% (range of 0% to 17%)

Target: <5%

Average amount of removed tissue with cancer cells at the edge

Coburn’s study: 28% (range of 15% to 50%)

Target: <5%

Source: Mahar AL, El-Sedfy A, Dixon M, Siddiqui M, Elmi M, Ritter A, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Jeong Y, Helyer L, Law C, Zagorski B, Coburn NG. Geographic variation in surgical practice patterns and outcomes for resected nonmetastatic gastric cancer in Ontario. Curr Oncol. 2018 Oct;25(5):e436–e443. doi: 10.3747/co.25.3953. Epub 2018 Oct 31.

__

2,200 Canadian men were diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2017.*

1,300 Canadian women were diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2017.*

Stomach cancer compared to breast cancer:

The five-year survival rate for stomach cancer is 25%.**

The five-year survival rate for breast cancer is 87%.**

3,500 Canadians were diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2017.*

26,300 Canadian women were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2017.*

2,100 Canadians died from stomach cancer in 2017.*

5,000 Canadian women died from breast cancer in 2017.*

*Source: Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, Provincial/Territorial Cancer Registries. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. Toronto (ON): Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics.

**Source: Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, Provincial/Territorial Cancer Registries. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2016. Toronto (ON): Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics.

__

South Korea, Mongolia and Japan had the highest rates of stomach cancer in 2018.*

6% of new cancer cases worldwide in 2018 were stomach cancer.*

50% of all stomach cancer cases occur in eastern Asia.**

*Source: Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Nov;68(6):394–424.

**Source: World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and stomach cancer. Continuous Update Project expert report. 2016. Revised 2018.

This work was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society, the Hanna Family Research Chair in Surgical Oncology, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Original article: Mahar AL, El-Sedfy A, Dixon M, Siddiqui M, Elmi M, Ritter A, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Jeong Y, Helyer L, Law C, Zagorski B, Coburn NG. Geographic variation in surgical practice patterns and outcomes for resected nonmetastatic gastric cancer in Ontario. Curr Oncol. 2018 Oct;25(5):e436-e443. doi: 10.3747/co.25.3953. Epub 2018 Oct 31.

In a nutshell

- A study led by Dr. Natalie Coburn shows variation in stomach cancer surgeries and patient outcomes in Ontario.

- Findings include differences in the number of lymph nodes examined and the rate of in-hospital deaths.

- The results stress the need to standardize treatment and for patients to ask care teams about their level of expertise.