Pregnancy complications can damage a woman's long-term heart health

Diabetes and high blood pressure during gestation are risk factors for cardiovascular disease even years later

September 12, 2018

Dr. Ilana Halperin at a postpartum education class for women who had gestational diabetes. She is raising awareness that complications like high blood sugar and high blood pressure are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The physiological changes a pregnant woman experiences are profound, putting her body under tremendous strain. By the end of the second trimester, for example, her heart pumps out 40% more blood to provide more oxygen and nutrients to the fetus, placenta and rest of her organs. Her kidneys work overtime, cleaning her blood, which grows in volume during pregnancy, and filtering out waste from the baby that is released into her bloodstream.

Meanwhile, the placenta, which nourishes the fetus, makes hormones that, although critical to the pregnancy, make the body less sensitive to insulin. To counteract this effect, the pancreas churns out extra insulin. When it can’t produce enough, glucose gets trapped in the blood, instead of being shuttled into the cells, causing high blood sugar. Pregnancy, then, can be thought of as a “stress test,” where vulnerabilities like diabetes or high blood pressure can be exposed. These complications, say researchers at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI), are not simply benign quirks of pregnancy, but rather harbingers of disease that call for action.

“If your metabolism and your pancreas aren’t able to handle the stress of pregnancy, and your blood sugars go up as a result, that’s a sign that other stressors, like getting older, may also lead to diabetes in the future,” says Dr. Baiju Shah, a scientist in the Schulich Heart Research Program at SRI and an endocrinologist at Sunnybrook.

Shah is researching the lasting impact of gestational diabetes, which develops near the end of the second trimester. He says that even though the condition goes away after delivery, it affects women and babies in the short and long term. Babies of women with gestational diabetes are bigger and at greater risk of birth trauma and staying in the neonatal intensive care unit. Moreover, one-half of all women with gestational diabetes develop Type 2 diabetes in their lifetime. These women are also more likely to have high blood pressure, high cholesterol and heart disease, notes Shah.

He is leading a study investigating whether the brief window of high blood sugars during gestational diabetes is associated with related problems like eye disease and kidney disease. “It was always thought that you just have three months of high blood sugars and that shouldn’t have any impact on your eyes or kidneys. But increasingly it’s been recognized that even people with mild blood sugar abnormalities that aren’t diabetes—slightly above normal [sugar levels]—maybe do have an increased risk for these complications. Gestational diabetes is similar to that; they have high blood sugars now, but may have had slightly abnormal blood sugars before that,” says Shah.

Dr. Ilana Halperin at a postpartum education class for women who had gestational diabetes. She is raising awareness that complications like high blood sugar and high blood pressure are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The researchers are conducting the first study to look at complications of gestational diabetes during pregnancy. They are analyzing images of the retina of women who have gestational diabetes, as well as those of women with a normal pregnancy. They are checking for hemorrhages in the retina, a sign of abnormal blood vessels in women with gestational diabetes. They are also measuring protein in the urine, as too much is a marker of kidney disease.

With patient recruitment complete, Shah is gathering results and will analyze the data for publication this year. He hopes that an upshot of the study is that women who’ve had gestational diabetes will be motivated to make healthy choices to prevent disease. “When you’re 35 it’s hard to think about heart disease in your 60s because it seems so far away. That’s why we’re trying to change that message a little bit, so that women are a little more aware.”

Equipping women with resources to help maintain health is a passion of Shah’s colleague, Dr. Ilana Halperin. A researcher at SRI in the Veterans Research Program and an endocrinologist at Sunnybrook, Halperin cares for pregnant women with diabetes—those who had it before pregnancy and those who developed it during pregnancy. Even though women with gestational diabetes are at much higher risk of developing diabetes later in life, Halperin notes that about only 30% get tested for high blood sugars after delivery. With reminders the screening rate can increase to 40%, but not all of these women attend postpartum education classes. She says low rates of postpartum diabetes screening and participation in classes are because women are preoccupied with caring for their children. “It’s a really busy time of life. Women have a hard time prioritizing their own health. We see a lot of patients who had gestational diabetes and then spent a couple years away from health care. They come back pregnant and actually have Type 2 diabetes, and they didn’t know they had it because nobody tested them between pregnancies.”

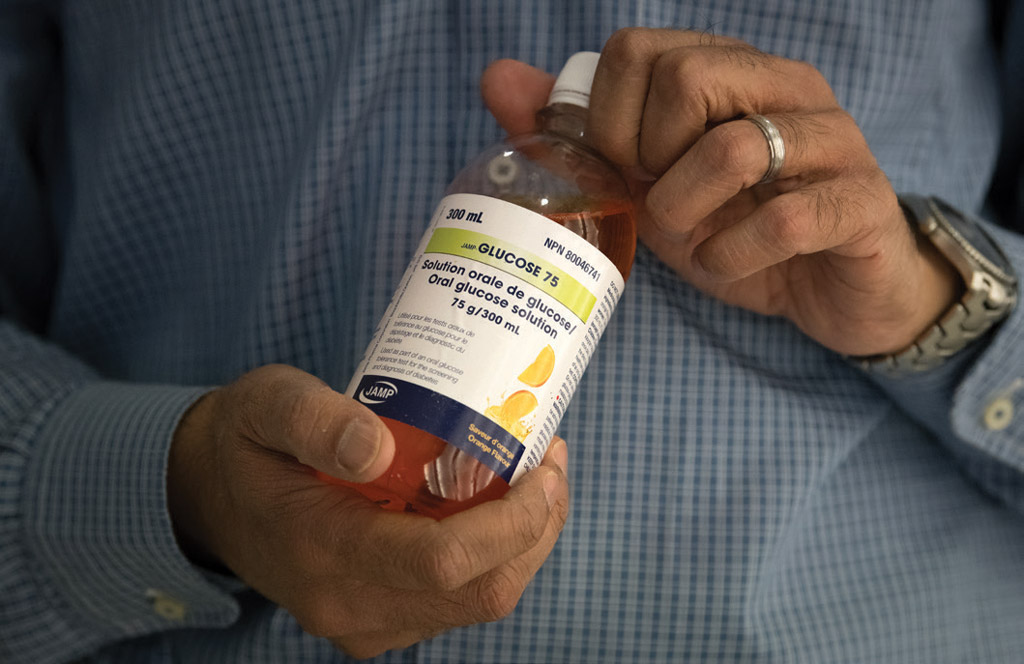

Dr. Baiju Shah holds a drink that is used in a screening test for high blood sugar during pregnancy. He is leading the first study to look at complications of

gestational diabetes during pregnancy.

She has partnered with Sunnybrook’s diabetes education centre to offer group visits to women with gestational diabetes. The classes are an opportunity to review the results of diabetes screening blood tests and offer education on lifestyle modification. Halperin notes that participants bring their children and enjoy brainstorming approaches to healthy living with other women. She attends part of the class to answer questions and provide one-on-one advice.

Halperin is the site investigator of a multicentre study called ADAPT-M, which stands for Avoiding Diabetes After Pregnancy Trial in Moms. Led by Dr. Lorraine Lipscombe at Women’s College Research Institute, the trial is comparing the effects of health coaching about diet and exercise with that of standard care (providing resources on healthy lifestyle without personalized coaching) in women who’ve had gestational diabetes. The interventions occur over six months and include education on healthy eating and exercise plans that are individually tailored and delivered through phone-based coaching and follow-up visits.

There were 105 women who completed the pilot study, 32 of whom were from Sunnybrook. The researchers are analyzing the data. “We’re looking at [the program’s] effectiveness in terms of outcomes—insulin resistance and weight after completing the program, and how feasible it is to train nurses and dietitians to be health coaches for this population and anyone who’s at risk for diabetes,” says Halperin.

She and Dr. Karen Fleming, a coinvestigator of the ADAPT-M study and division lead of family medicine obstetrics at Sunnybrook, are raising awareness that pregnancy complications like gestational diabetes and high blood pressure are risk factors for cardiovascular disease. “It’s not really well understood by women or primary care providers that what happens in pregnancy doesn’t just stay in pregnancy,” says Fleming.

In 2014, Fleming established the 4P Post Partum Maternal Health Clinic at Sunnybrook for women whose pregnancies were complicated by high blood pressure. The clinic offers counselling and education to improve health by targeting poor diet, lack of exercise and smoking. Fleming says that focusing on these areas significantly reduces the risk of heart disease, and that interventions are particularly important because heart disease is often viewed as a diseaseof older men. “We’re not so good with women and heart disease. We’re less likely to investigate; we’re less likely to treat with cholesterol-lowering drugs; we’re less likely to refer them to cardiac rehab; and they’re less likely to stay in cardiac rehab. And heart disease is the number one cause of death in women,” says Fleming.

There’s also room for improvement in the relaying of pregnancy history to family doctors. There’s no standardized process for documenting gestational hypertension and diabetes in a patient’s electronic medical record, notes Fleming, who says that it’s either up to the patient to let her doctor know, or the family doctor needs to know to ask about issues arising during the pregnancy.

Her research bears this out. Her team conducted a survey of female patients of the Sunnybrook Academic Family Health Team to determine if pregnancy history is captured in the electronic medical record and whether primary care practices are identifying and screening women with pregnancy complications like high blood pressure and gestational diabetes. Of the 223 survey responses received, one-quarter of the women reported having a pregnancy complication. Of these, 25% said there was no discussion of future health concerns by their obstetrician or family doctor during a post-delivery visit. The next step is to develop a “prompt” function in patient electronic medical records to remind family doctors to inquire about their patient’s pregnancy history.

To raise patients’ awareness of this issue, she and her colleagues produced a postcard that is given to discharged patients. It prompts women to notify family doctors of any pregnancy complications and contains a link to online health education resources. Sunnybrook’s family medicine obstetrics team now also sends a letter to the family doctors of women who’ve had complications during pregnancy. The letter lists the complication(s), summarizes the delivery and contains a referral to an education program. It also highlights the patient’s risk for future cardiovascular disease and clinical recommendations regarding subsequent pregnancies.

One thing women can do to prevent pregnancy complications in the first place is to exercise, says Fleming. “You’re having a baby. The last thing you want to do is enter the pushing part of labour having been inactive. If you’re asking what can you do that’s going to make a difference, the answer is be active and exercise,” she says. She also notes that in addition to reducing rates of gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders, exercise lowers rates of caesarean sections and depression in pregnancy. One of the challenges of encouraging exercise in pregnancy is countering false notions. “The trick is trying to engage women to be active because people are fearful. For many, pregnancy is a time where you’re encouraged to put your feet up and rest,” says Fleming. She recommends regular low-impact exercise prenatally, unless doing so poses a risk of harm.

Fleming is helping to write the new Canadian guidelines on exercise in pregnancy, which will be published in 2018. The current guidelines, published in 2003, apply only to women with low-risk pregnancies. The updated guidelines will be relevant to more women and are based on extensive research. “We know not everyone is low-risk. Almost one-half of women have a body mass index of over 25 when they come into pregnancy. So what are the recommendations for different populations of people?” says Fleming.

Dr. Karen Fleming is helping to write the new Canadian guidelines on exercise in pregnancy, which will be published in 2018.

In her practice, she sees elite athletes and professional dancers who are pregnant (she delivered both of the National Ballet of Canada’s Heather Ogden’s babies), and has surveyed Masters swimmers in partnership with Masters Swimming Canada. She found that many were exercising beyond current exercise guidelines and 25% of them competed while pregnant. There were no reported cases of gestational diabetes and low rates of operative deliveries. Fleming also found that, in many cases, these women were receiving guidance on exercise in pregnancy from coaches, not their doctors. This led to a survey of the coaches, who expressed an interest in online education modules to help them meet the needs of their athletes.

For pregnant women who struggle to access resources on education and exercise, Fleming collaborated with colleagues from Michael Garron Hospital and Thorncliffe Neighbourhood Office to offer yoga classes and group education in Thorncliffe Park, a community that is densely populated with newcomers to Canada. The pilot program, which also provided child care, resulted in increased rates of physical activity among the participants. For women with barriers to attending education classes, she is looking into the use of technology, including online modules and virtual support groups. These are the kinds of initiatives that Halperin says are needed to prevent chronic disease. “Most people I talk to say, ‘I know I need to exercise more and eat better, but I’m a working mom with two small kids. I can’t find the time.’ It’s about the public health changes we need to do to make [having a] healthy lifestyle more accessible,” she says.

Fleming’s research was supported by Michael Garron Hospital, Sunnybrook and the University of Toronto. The ADAPT-M study, of which Fleming and Halperin are a part, is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Shah’s research is funded by CIHR.