Researchers target tough-to-treat brain diseases with focused ultrasound

Noninvasive imaging technique makes major gains in studies

Researchers at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI) have shown that it’s possible to open the blood-brain barrier in people with Alzheimer’s disease safely and repeatedly with MRI-guided focused ultrasound. The noninvasive technology used very low power sonic energy to open the blood-brain barrier and target areas of the brain where amyloid, the “sticky” plaque that signposts the disease, was located.

Results were published July 25, 2018, in Nature Communications. Dr. Nir Lipsman, neurosurgeon, scientist and director of the Harquail Centre for Neuromodulation, led the study with Dr. Sandra Black, neurologist, senior scientist and director of the Hurvitz Brain Sciences Research Program.

Launched in May 2017, the small trial recruited five patients who had amyloid in their brains and scores on a cognitive test that reflected mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

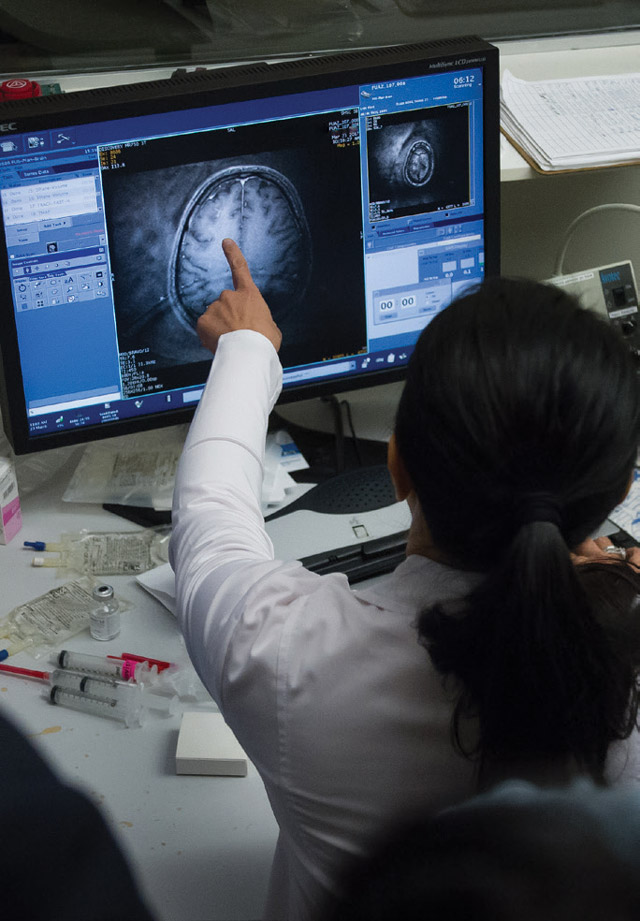

During the procedure, patients were fitted with the brain device, which looks like a helmet, and put into an MRI scanner, so that the team could guide and monitor the ultrasound delivery.

Sunnybrook scientists have published the first clinical study showing that focused ultrasound can be used to open the blood-brain barrier safely and repeatedly in Alzheimer’s disease.

Focused ultrasound works by directing sound waves on a target. For the blood-brain barrier, when paired with microbubbles injected intravenously, that sonic energy has the effect of opening the barrier, which otherwise is drum tight to make sure no toxins get into the brain—the flip side of which is that almost no therapies can get in, either.

Within seconds, the blood-barrier was open, and focused ultrasound had reached its target. One month later, patients were treated in the same area but at twice the volume. After each procedure, next-day MRI scans confirmed the blood-brain barrier had closed. There were no serious adverse effects.

This advance is a crucial step toward being able to treat diseases with few, if any, options. Chief among these is Alzheimer’s disease; by 2050, 12 million North Americans are likely to be living with this progressive illness.

In other world-first trials, the SRI team is evaluating the safety of focused ultrasound in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, which kills two to three people per day in Canada. Brain cancer, too, is under scrutiny, including a trial of focused ultrasound and chemotherapy in glioblastoma, the cancer that took the life of Gord Downie, as it does 96% of people within five years of diagnosis.

On the strength of the Alzheimer’s disease trial results, scientists have turned to a next-phase clinical trial, which will recruit more patients and target a different area of the brain.

Sunnybrook Research Institute has the world’s most extensive program of focused ultrasound research. Led by Dr. Kullervo Hynynen, director of Physical Sciences at SRI, who pioneered the technology, physicists, engineers, biologists, neuroscientists and clinicians are working to advance development of the technology; study the mechanisms of how it works, alone and with therapeutics; and lead clinical trials of it.

Depression is also of intense interest. In May 2018, Lipsman launched a trial using focused ultrasound in a different way, as a kind of scalpel-free neurosurgery. When used this way, the beams have slightly higher power, enough that they can, with utmost precision, destroy problem-causing targets in the brain. The trial seeks to help people with a severe form of the disease for whom other treatments have failed. It follows the 2017 launch of a similar trial in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Elsewhere in the central nervous system, in the spinal cord, SRI scientists have made a key discovery. Dr. Meaghan O’Reilly and Dr. Arjun Sahgal of Physical Sciences showed that using focused ultrasound to sneak a drug into the spinal cord of rats worked to ambush tumours there.

The therapy shrunk by about two-thirds a kind of tumour where cancer spreads from its original site to the cerebrospinal fluid and membranes covering the brain and spinal cord.

The study was published in Scientific Reports in June 2018. Apart from being able to treat tumours where palliation is the norm, results have implications for studies into spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative disease.